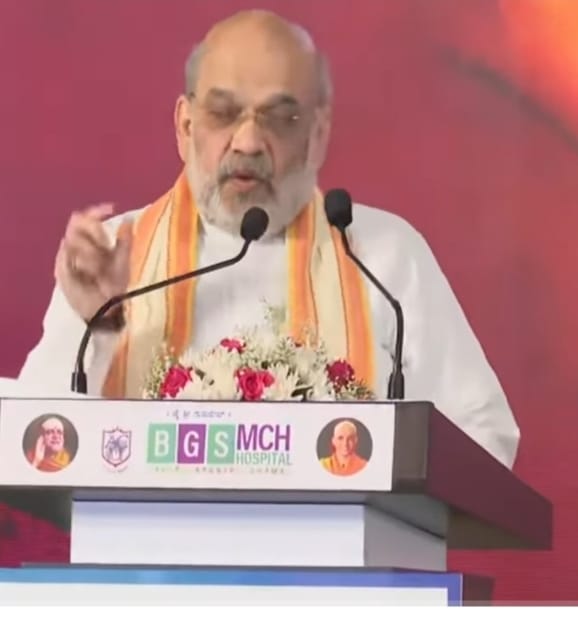

Polarizing Remark Sparks Controversy

At a book launch in New Delhi on Thursday, June 2024, Union Home Minister Amit Shah ignited a linguistic firestorm by asserting that a time would soon arrive when those speaking English in India would “feel ashamed.” Shah emphasized that India’s native languages are the “ornament of our culture, stating, “Without them, we would not have been Bharatiya. Our country, its history, its culture, our Dharma, if these have to be understood, it cannot be done in foreign languages.” This provocative statement has drawn sharp criticism, reigniting a decades-old debate over the place of English in India’s diverse linguistic landscape.

Lok Sabha Leader of Opposition Rahul Gandhi swiftly responded, framing English as a tool of empowerment rather than a source of shame. “English is not a dam, it is a bridge. English is not shameful, it is empowering. English is not a chain—it is a tool to break the chains,” he said. Other opposition leaders, including TMC MPs Derek O’Brien O’Brien and Sanjay Gupta, also condemned Shah’s remarks, highlighting the divisive nature of his comments.

Echoes of a Historical Debate

Shah’s statement evokes memories of a contentious decision made 35 years ago by former Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Mulayam Singh Yadav. In May 1990, Yadav banned the use of English in the state, arguing that it was the “language of foreigners and the elite,” perpetuating socio-economic disparities and fostering a superiority-inferiority complex. His “Angrezi Hatao” (Remove English) campaign sought to eliminate English from public life, even aligning with Urdu-speaking communities to counter opposition to Urdu, which had itself been a lightning rod of controversy when granted second official language status in Uttar Pradesh in the early 1990s. Yadav’s paradoxical stance—opposing English while defending Urdu—underscored the complex interplay of language and politics in India.

This anti-English sentiment traces its roots to the 1950s, when socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia championed the removal of English from official use in Uttar Pradesh. Even earlier, Mahatma Gandhi and the Congress party viewed English as a colonial imposition that displaced indigenous languages. Post-independence, the Constitution designated Hindi as the official language but retained English for administrative purposes for a transitional period of 15 years. This pragmatic decision acknowledged India’s India’s linguistic diversity and the need for a unifying link language. However, attempts to impose Hindi in southern states during the 1960s backfired, deepening the North-South linguistic divide.

The Legacy of “Angrezi Hatao”

The “Angrezi Hatao” movement gained traction through leaders like Morarji Desai, who, as Bombay’s chief minister in 1954, proposed restricting English-medium education to those with English as their mother tongue. Though his plan failed, it fuelled Lohia’s broader campaign for a Hindi-speaking nation. Lohia condemned English as a colonial relic that stifled original thought and hindered universal education. He advocated for education and governance in regional languages, though he made concessions for southern states to use English English for inter-state communication for 50 years.

Lohia’s ideas, however, were often distorted by his followers. In Uttar Pradesh, English was banned in the 1950s and again in the 1980s. In Bihar, Chief Minister Karpoori Thakur’s government in the 1970s relegated English to an optional subject, resulting in a “Karpoori class” matriculation devoid of English proficiency. A decade later, Mulayam Singh Yadav revived this campaign, with unintended consequences. Christian institutions, accused of using English to promote conversions, faced attacks, despite many native Christians not speaking English. This conflation of English with Christianity mirrored the erroneous association of Urdu with Muslims, revealing the irrationality of linguistic zealotry.

English as a Catalyst for Progress

Despite its colonial origins, English has played a pivotal role in shaping modern India. Introduced by the British to create a class of administrative clerks, it inadvertently fostered a Western-educated Indian middle class that spearheaded the national movement. Leaders like Raja Rammohun Roy, Dadabhai Naoroji, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Mahatma Gandhi, and Jawaharlal Nehru, educated through English, drew inspiration from Western ideals of nationalism, democracy, and liberty. English English also facilitated advancements in science, technology, law, and governance, becoming a conduit for India’s India’s engagement with the world.

Over time, English has transcended its foreign roots to acquire a distinctly Indian character. It is the mother tongue of a recognized minority and the official language of Nagaland. In cosmopolitan cities like Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, Hyderabad, and Bengaluru, English English embodies a secular, inclusive spirit, unbound by religion, caste, or community. Its dominance in education, business, industry, and administration—evident even in the Hindi heartland—underscores its integration into India’s fabric.

The Irony of Anti-English Rhetoric

Ironically, many proponents of the anti-English movement, including political leaders, enroll their children in English-medium schools, recognizing the language’s practical advantages. India’s India’s progress in the global arena, from technology to trade, owes much to English-medium education. Statistically, English outpaces other languages in key sectors, cementing its status as an indispensable tool for upward mobility.

Amit Shah’s Shah’s remarks risk stoking linguistic tensions at a time when unity is paramount. English, far from being a source of shame, is a symbol of India’s India’s cosmopolitan identity and global aspirations. Any attempt to marginalize it could trigger a resurgence of inter-linguistic conflicts, threatening the delicate balance of India’s India’s diverse cultural landscape.

A Call for Linguistic Harmony

Languages should unite, not divide. English, as the world’s lingua franca, is a bridge to opportunity and a testament to India’s India’s ability to adapt and thrive. Rather than vilifying it for political gain, leaders like Amit Shah should champion linguistic inclusivity, recognizing English alongside India’s India’s rich tapestry of languages. In a globalized world, disowning English for narrow political ends is not just short-sighted—it is a disservice to the nation’s future.

India’s strength lies in its diversity, and English is a vital thread in this vibrant mosaic. By embracing it as a tool of empowerment, India can continue to swim with the tide of progress, rather than against it.

(Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai)