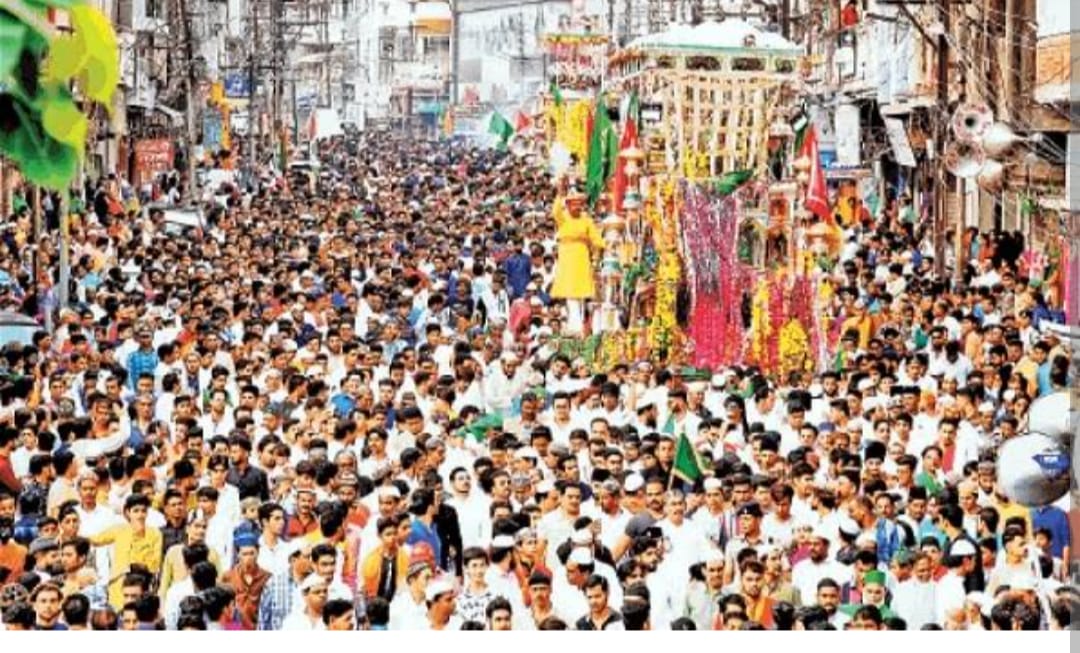

As the Islamic world observes Ashura on July 6, 2025, the 10th day of Muharram, the solemn remembrance of the martyrdom of Imam Hussain at Karbala resonates deeply in Lucknow, a city synonymous with the Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb—a cultural synthesis of Hindu and Muslim traditions. At the heart of this syncretic heritage stands Munshi Channu Lal Dilgeer (1780–1848), a Hindu poet whose poignant marsiyas and nohas, particularly the evocative “Ghabrayegi Zainab,” capture the universal grief of Karbala while embodying the spirit of communal harmony. Dilgeer’s contributions to Urdu literature and Muharram rituals remain a testament to the inclusive ethos of Awadh’s cultural landscape.

A Hindu Poet’s Devotion to Karbala

Channu Lal Dilgeer, born in Lucknow during the reign of Nawab Asaf-ud-Daulah, was a figure steeped in the literary and cultural vibrancy of Awadh. The brother of Raja Jhaulal, deputy prime minister under the Nawab, Dilgeer grew up in an environment that fostered intellectual and artistic excellence. His early forays into poetry focused on romantic genres like ghazals and masnavis, under the pen name “Tarab.” However, inspired by his brother’s reverence for the martyrs of Karbala and the tragic narratives of Imam Hussain, Dilgeer underwent a profound transformation. He embraced the Imamia faith, adopting the name Ghulam Hussain and the takhallus “Dilgeer,” meaning “heart-stricken.” This shift marked a complete dedication to marsiya and salam poetry, culminating in the destruction of his earlier romantic works, which he cast into Moti Jheel.

Dilgeer’s conversion and his immersion in the stories of Karbala reflect the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, a cultural ethos where religious boundaries blurred in the pursuit of shared humanity. Like Ras Khan, the 16th-century poet who composed bhajans for Lord Krishna, Dilgeer’s devotion to Imam Hussain transcended communal divides, making him a revered figure in Lucknow’s azadari (mourning) traditions.

The Poetic Genius of Dilgeer

Dilgeer’s literary prowess earned him acclaim in the courts of Awadh’s Nawabs. A disciple of celebrated poets like Mirza Khani Nawazish and later Nasikh, he was a contemporary of luminaries such as Mir Khaliq and Mirza Fasih. His inability to recite his own compositions due to a speech impairment did not diminish their impact; his marsiyas were widely recited in majlises (mourning gatherings) during the reigns of Nawabs Ghazi-ud-Din Haider and Mohammad Ali Shah. The latter honoured him with 400 rupees for a masnavi praising Hussainabad, a testament to his stature.

Dilgeer’s oeuvre, as documented in ‘The Making of Awadh Culture’ by Madhu Trivedi, includes over 500 marsiyas, with his collection Majmua Marasi Mirza Dilgeer published by Munshi Nawal Kishore Press and preserved at Lucknow University’s Tagore Library. His poetry was lauded for its linguistic precision and emotional depth, with contemporaries like Mirza Dabeer acknowledging his mastery. Dabeer’s remark—“It indeed would have been a great honor for me, had Dilgeer been my Ustad”—underscores the reverence Dilgeer commanded. Some even speculated that Dilgeer was Dabeer’s mentor, a notion Dabeer did not refute, highlighting Dilgeer’s influence in shaping Urdu marsiya traditions.

“Ghabrayegi Zainab”: A Lament for Humanity

Among Dilgeer’s most enduring works is the marsiya “Ghabrayegi Zainab,” a heartrending elegy recited globally during Shaam-e-Ghareeban, the evening after the Battle of Karbala when the survivors, led by Zainab, faced the desolation of their loss. The marsiya narrates the anguish of Zainab, daughter of Hazrat Ali and Fatima, as she returns to a ravaged home after the martyrdom of her male kin—Imam Hussain, Qasim, Abbas, Akbar, and the infant Ali Asghar. Its repetitive refrain, “Ghabrayegi Zainab” (Zainab will be agitated and lost), captures her overwhelming grief and disorientation.

The marsiya’s six stanzas, each a musaddas (six-line poem), weave a tapestry of sorrow. The first stanza laments Zainab’s futile search for her brother Imam Hussain: “O, brother, where will she find you when she gets home?” The second depicts the desolation of a once-vibrant household: “How this once bustling house stands empty, visited by destruction.” Subsequent verses mourn the absence of Qasim, Abbas, and Akbar, question the marks of captivity on Zainab’s arms, and foresee her heart breaking at the memory of her brother. The final stanza reflects on her public humiliation and imprisonment, pondering, “Who knows how much more Zainab has to bear?”

Dilgeer’s use of simple yet evocative Urdu imbues the marsiya with universal resonance, making it a staple in Muharram majlises. Its emotional intensity mirrors the tragedy of Karbala, where Imam Hussain’s stand against Yazid’s tyranny became a symbol of resistance, compassion, and dignity. By offering water to the enemy’s soldiers and horses despite his own caravan’s scarcity, Imam Hussain exemplified humanity, a theme Dilgeer’s poetry amplifies.

Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb and Karbala’s Universal Message

The story of Karbala, central to Shia consciousness, transcends religious boundaries, embodying universal values of justice, sacrifice, and compassion. Dilgeer’s marsiyas, particularly “Ghabrayegi Zainab,” reflect this universality, resonating with audiences across faiths. His work exemplifies the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, where Hindu and Muslim poets alike contributed to Urdu literature’s golden age in Awadh. Under the Nawabs, marsiyas evolved from short elegies to extended compositions, with poets like Mir Zamir introducing vivid metaphors and battle scenes, a tradition Dilgeer enriched with his emotive and accessible style.

Dilgeer’s contributions were part of a broader cultural milieu where non-Muslim poets like Josh Malihabadi also expressed devotion to Imam Hussain, as seen in the verse: “Insaan Ko Bedaar To Ho Lene Do, Har Qaum Pukaregi Hamare Hain Hussain” (Let humanity awaken, every community will claim Hussain as their own). This syncretism was nurtured by Awadh’s rulers, who extended mourning periods to 40 days and patronized marsiya recitations, fostering an environment where poets like Dilgeer thrived.

The Legacy of the “Terhi Qabr”

Dilgeer’s grave, known as the “Terhi Qabr” (Tilted Grave) near Nakhas’ Chiriya Bazar in Lucknow, remains a site of reverence, though its significance is often misunderstood. Locals venerate it as the resting place of a “Shaheed Mard” (martyr), unaware of Dilgeer’s identity as a poet. Historian Agha Mehdi noted that Dilgeer’s house in Kanghi Wali Gali had fallen into ruins, but his grave endures as a symbol of his devotion. The lack of a display board or formal recognition of his contributions highlights a tragic oversight by Lucknow’s azadari community, which continues to thrive globally.

Dilgeer’s legacy, however, lives on through his poetry. His marsiyas, recited in majlises worldwide, keep alive the memory of Karbala’s martyrs and the values they represent. His construction of an imambara during Ghazi-ud-Din Haider’s reign and his masnavi on Hussainabad reflect his deep commitment to azadari, earning him the metaphorical title of “martyr without martyrdom.”

A Call for Remembrance

As Lucknow prepares to commemorate Ashura, Dilgeer’s story serves as a poignant reminder of the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb’s enduring relevance. His marsiyas, particularly “Ghabrayegi Zainab,” bridge religious divides, uniting communities in shared grief and admiration for Imam Hussain’s sacrifice. The apathy toward Dilgeer’s legacy—evident in the neglect of his grave and the absence of seminars or mehfils in his honor—calls for renewed efforts to celebrate his contributions. Organizing annual events to honor Dilgeer could reinvigorate interest in his work, ensuring that his poetry continues to inspire future generations.

In a world often divided by faith, Dilgeer’s life and work stand as a beacon of unity. His verses, steeped in compassion and humanity, echo the message of Karbala—a call to uphold justice, dignity, and mutual respect. As we mourn on Ashura, let us also celebrate Channu Lal Dilgeer, a Hindu poet whose heart was captivated by Imam Hussain, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural and literary heritage of Awadh.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai