If a Dalit is forced into the silence of the self, crushed beneath the weight of history and ignored by a world that surrounds yet refuses to see them, what are they to do? Perhaps nothing. Yet in that apparent inertia lies the tragedy: the descent into a quiet anguish, a deepening katzenjammer that haunts generations. Seeking solace, dignity, and identity—not on some mountain peak or riverbank, but in the still, slumberous eyes of the self—a whole community searches for a place in a world that has long denied them one.

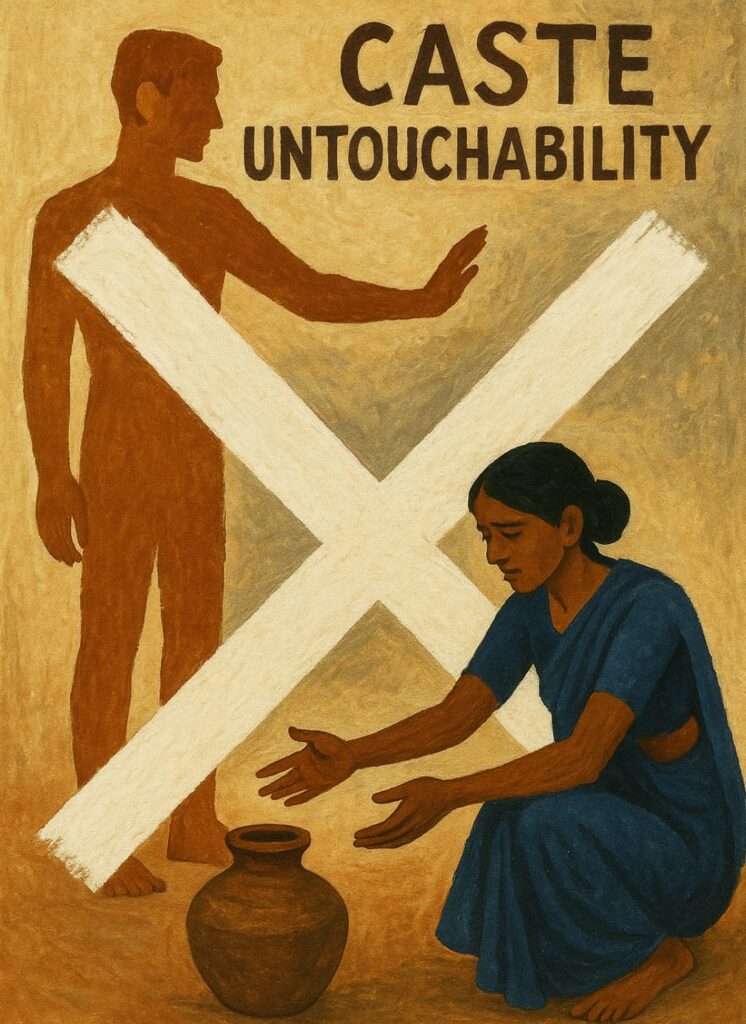

Is descent truly a justification for humiliation? For discrimination? For violence? The caste monopoly, entrenched in Brahminical hegemony, has historically dismissed Dalits as nothing more than insects crawling toward their designated ghettos, pariah quarters, and squalid existence. The oppression is not accidental; it is systemic, woven into the social and political fabric of India.

What is often called “Dalit literature” finds its roots in the revolutionary ideas of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. His call for the annihilation of caste dismantled the barriers of an entire mass of people across South Asia and ushered them into an insurrectionary consciousness. Yet, post-independence India left Dalits on the margins, living off leftovers while upper-caste elites flaunted their privilege. India may have been free, but Dalits were not.

The lingering question—posed by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and echoed in every corner of subaltern studies—remains: Can the subaltern speak? By the late 20th century, this predicament had only deepened, leaving many Dalits horrified and driving them to seek refuge in religions like Buddhism and Christianity, where caste hierarchies held less sway.

Dr. Ambedkar, having seen that the caste system would never treat Dalits as full human beings, emerged as the undisputed leader of the downtrodden. His exhortation to resist, agitate, and educate became the cornerstone of Dalit awakening. The first visible spark of political insurrection came in Maharashtra in 1972 with the formation of the Dalit Panthers, inspired by the Black Panthers in the United States. Founded by J.V. Pawar and Namdeo Dhasal, among others, the Dalit Panthers represented the first organized literary and political resistance against a hostile socio-political order.

In the Dalit context, activism was never about terror—it was about survival and dignity. Apart from Buddhism, many Dalits were drawn to Marxism. Large-scale conversions occurred in Kerala and parts of Tamil Nadu, where Christianity offered a more egalitarian refuge. Ambedkar’s mission to break Dalit silence found its voice through literature. Maharashtrian writers led this charge, even as mainstream Hindi literature remained largely indifferent, treating Dalit writings with disdain and contempt.

Works such as Flaming Feet by D. R. Nagaraj, No Alphabet in Sight by K. Satyanarayana, and Identity Card by S. Joseph stand as landmark publications, igniting Dalit consciousness. The red mark on the Dalit identity card—a symbol of humiliation—became a rallying point as Dalits consolidated through literature. Movements like the Adi Dharam in Bengal, Narayan Swami in Kerala, and the Adi Dalit movement in Tamil Nadu further helped Dalits emerge as dignified social entities, discarding the sexist and hierarchical predilections embedded within Hindu caste orthodoxy.

Ambedkar’s fiercest moment of dissent came when he was denied the platform to speak at a public function. The undelivered speech became the legendary Annihilation of Caste, a blistering indictment of the ruling class and its refusal to grant socio-political space to Dalits. His words carried the weight of centuries of subjugation.

Even personal narratives reflect this entrenched caste discrimination. Om Prakash Valmiki, for instance, was not allowed to sit in his school classroom; instead, he was assigned sweeping duties by his headmaster. That humiliation became the fuel for his literary work, most notably Joothan and the poem Thakur Ka Kuan. While Premchand also wrote about Dalit experiences, such as in Thakur Ka Kuan and Kafan, his portrayals have been critiqued by Dalit writers like Arjun Dangle and Daya Pawar for perpetuating negative stereotypes. In Kafan, for instance, the characters Madhav and Ghesu—portrayed as indifferent to a woman’s death—are seen as an unfair dehumanization of Dalits.

Dalit writers argue that Premchand’s depictions pale in comparison to the raw, honest accounts presented in Dalit literature. Writers like Arjun Dangle, Bandhu Madhav, Madhav Desai, and Babulal Bagul have openly questioned these mainstream narratives. For them, Ambedkar remains central to Dalit identity—not only as a politician and social reformer but as the catalyst for a literary revolution.

In the 1950s, the first wave of Dalit graduates emerged from Ghanshyam Talwatkar College. Together, they formed the Siddharth Sahitya Sangh, contributing to a literary and social movement that echoed through Marathi literature. Publications like Prabuddha Bharat (linked to the Scheduled Castes Federation) played a pivotal role. Paradoxically, even within this emergent literature, Brahmin writers like V.S. Khandekar and N.S. Phadke held influence, highlighting the complex dynamic between dominant and subaltern voices.

The 1960s marked a crucial phase in Marathi literature’s evolution. Writers like Narayan Surve, Annabhau Sathe, and Shankar Rao Kharat propelled movements like the Little Magazine Movement and introduced the figure of the “Angry Young Man” into Dalit literary discourse. Annabhau Sathe’s revolutionary poem famously declares:

“Take a hammer to change the world,

Saying went Bhimrao.”

This clarion call urged Dalits to rise in revolt against a caste-ridden society that celebrated democracy while practicing social apartheid. Poisoned Bread, an anthology edited by Arjun Dangle, brought together poems, autobiographical essays, short stories, and speeches to assert that Dalit literature does not need validation from mainstream literature—it stands as its own powerful form of expression.

Despite some progress through reservation policies in education and employment, Dalits still face systemic social injustice. Beena Pallical rightly observes:

“Injustice directed at Dalits causes profound trauma and suffering across generations. Stigma follows an individual from birth until death, affecting all aspects of life—from education and housing to access to justice and political participation.”

Dalit literature shares striking parallels with Black literature in Africa and America. Just as African writers like Chinua Achebe, Ben Okri, Alex La Guma, and Alan Paton documented the struggles against white supremacy, segregation, and apartheid, Dalit writers have chronicled their own battles against caste oppression. Works like Things Fall Apart and The Famished Road elevated African consciousness, while writers such as James Baldwin and Richard Wright gave voice to Black humanity’s collective struggles.

The dilemmas faced by India’s subaltern classes are no less profound. Lynchings, caste atrocities, and social exclusion continue to scar the nation’s conscience. The remains of feudal overlordship persist as grim reminders of a brutal social structure.

The enduring question posed by Spivak—”Can the subaltern speak?”—echoes hauntingly across both continents and histories. While Spivak argues they cannot, Dalit literature suggests otherwise. Through the audacious prose of Daya Pawar, the searing poetry of Om Prakash Valmiki, and the determined activism of Dalit Panthers, the subaltern has spoken—and continues to do so. Their voice may not yet have dismantled the entrenched hierarchies, but it has forced the nation, and indeed the world, to listen.

[Dr Afroz Ashrafi is a Faculty Member in the Department of English at The College of Commerce, Arts and Science University, PatiliPutra ]