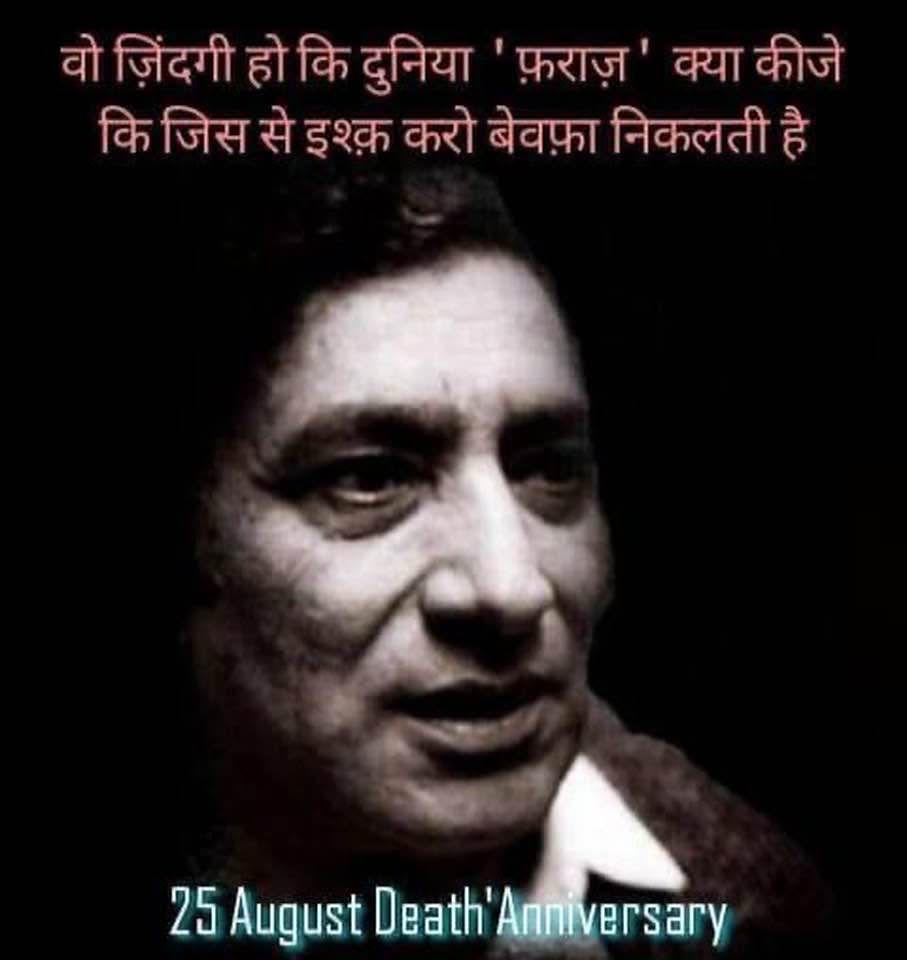

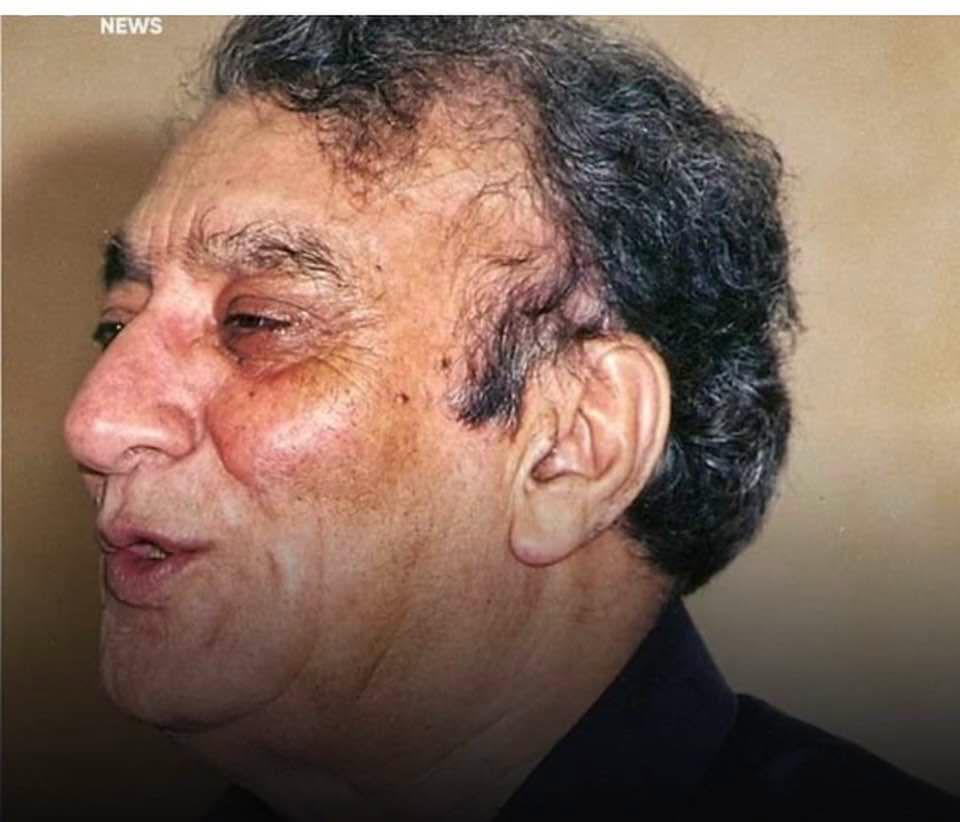

Twin Flames of Urdu: Remembering Makhdoom Mohiuddin and Ahmad Faraz .On 25th August, the death anniversary of two titans of poetry, we revisit how they made love and rebellion inseparable in Urdu literature

A Shared Date, A Shared Destiny

Some dates in history acquire a strange resonance. 25th August is one such day in the literary calendar of South Asia. On this date, two extraordinary voices of Urdu poetry—Makhdoom Mohiuddin (1908–1969) and Ahmad Faraz (1931–2008)—departed this world, separated by nearly four decades yet united by their spirit of resistance and romance.

Both men lived in different geographies—Makhdoom in Hyderabad, India, and Faraz in Peshawar and later Islamabad, Pakistan. Yet their poetic journeys ran in parallel, each weaving love and revolution into the fabric of Urdu. Each refused to surrender to tyranny, whether it was feudalism, colonialism, dictatorship, or authoritarian silence. And each left behind a corpus of verse that continues to inspire lovers, students, workers, and dreamers across South Asia.

Their shared death anniversary invites us to read them together—not merely as individual poets but as twin flames of a literary tradition that blurred the lines between sighs and slogans, kisses and revolts.

Makhdoom: The Red Dawn of Hyderabad

Born on 4 February 1908 in Medak district of the princely state of Hyderabad, Makhdoom Mohiuddin was destined to be both a lover and a rebel. He completed his education at Osmania University, where he stood out for his charisma and wit. By the early 1930s, he was already writing ghazals, but unlike many of his contemporaries, he quickly expanded from romance to revolution.

The world was in turmoil—the rise of fascism in Europe, the shadow of colonialism in India, and the suffocating feudalism of Hyderabad. Makhdoom’s pen could not remain silent.

“Woh azadi, azadi kya

Mazdoor ka jismein raaj na ho?”

What freedom is that, if the workers do not rule?

This was the cry that turned his poetry into marching songs for the oppressed.

In 1936, he became a founding member of Hyderabad’s unit of the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA), alongside names like Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Sajjad Zaheer, Krishan Chander, and Ismat Chughtai. For Makhdoom, poetry was not mere ornamentation; it was a weapon, a way to mobilise hearts against injustice.

Faraz: The Lofty Voice of the Frontier

Ahmad Faraz, born Syed Ahmad Shah in Kohat on 12 January 1931, inherited from his rugged frontier homeland both lyricism and resilience. Educated at Edwardes College, Peshawar, he specialised in Persian and Urdu literature. Choosing the pen name “Faraz”—meaning loftiness—he soon soared in the skies of Urdu poetry.

His early verses established him as a romantic voice of longing and delicacy:

“Suna hai log usay aankh bhar ke dekhte hain,

So uske sheher mein kuch din thehar ke dekhte hain.”

I hear people gaze at her with unblinking eyes,

Perhaps I too should linger in her city awhile.

But history would not allow Faraz to remain only a romantic. The dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq in the late 1970s and 80s demanded courage from intellectuals. Faraz chose defiance. He was imprisoned, exiled, and yet never silenced.

Love as Resistance

Both Makhdoom and Faraz refused to draw strict boundaries between romance and revolution. For them, the beloved was often a metaphor—sometimes a person, sometimes the homeland, sometimes freedom itself.

Makhdoom’s “Surkh Savera” (The Red Dawn) captured this fusion: the fragrance of jasmine mingled with the odour of gunpowder. His lines could move effortlessly between tenderness and militancy:

“Main tere pyar mein jalta raha, jalta hi raha,

Aur log kehte rahe ke yeh charagh jal raha hai.”

I kept burning in your love, burning endlessly,

While people thought it was just a lamp aglow.

Faraz, too, made romance a metaphor for rebellion. His most iconic ghazal, sung by Mehdi Hassan, became an anthem of both longing and resilience:

“Ranjish hi sahi, dil hi dukhane ke liye aa,

Aa phir se mujhe chhod ke jaane ke liye aa.”

Come, even if only to grieve my heart once more,

Come, if only to leave me again as before.

What could be more political than insisting on the beloved’s return, even if betrayal is inevitable? In this paradox, Faraz mirrored the citizen’s relationship with a nation that wounds yet is still loved.

Poets in the Arena of Politics

Makhdoom’s life was inseparable from political struggle. He gave up an academic career to become a full-time member of the Communist Party of India. He led workers in Hyderabad, became an intellectual voice of the Telangana Armed Struggle, and eventually entered the legislature. His pen and his politics were aligned—both fought for the same cause: “Victory for Love and Labour.”

Faraz, meanwhile, used poetry as political dissent. Arrested for his bold verses under Zia, he endured exile in Europe and Canada. Yet even as he rose to head institutions like the Pakistan Academy of Letters, he never compromised his independence. At moments of political injustice, he resigned rather than conform.

Voices Immortalised in Song

A crucial reason for their enduring popularity is the way their verses travelled into music.

Makhdoom’s ghazals entered Bollywood, carried by haunting voices:

• “Aap Ki Yaad Aati Rahi Raat Bhar” (Jagjit & Chitra Singh, Gaman, 1978)

• “Phir Chhidi Raat, Baat Phoolon Ki” (Lata Mangeshkar & Talat Aziz, Bazaar, 1982)

Faraz’s poetry became the soul of the ghazal mehfil. Sung by Mehdi Hassan, Noor Jehan, Ghulam Ali, Jagjit Singh, and others, his lines crossed borders with ease.

“Ab ke hum bichhde to shaayad kabhi khwabon mein milein,

Jis tarah sookhe hue phool kitaabon mein milein.”

If we part now, perhaps we’ll only meet in dreams,

Like pressed flowers found in forgotten books.

Between Prison and Exile

Makhdoom endured prison; Faraz endured exile. Yet both turned suffering into strength.

Makhdoom’s prison poems, like “Qaid”, infused Urdu with the anguish and dignity of resistance. Faraz’s exile deepened his longing, producing verses that resonate with anyone who has known displacement.

Death and Remembrance

Makhdoom died on 25 August 1969 in Delhi while attending a CPI National Council meeting. He was laid to rest in Hyderabad, where Makhdoom Bhavan now bears his name.

Faraz died on 25 August 2008 in Islamabad, after a long illness. He was buried with state honours, mourned by thousands.

Both men left this world on the same date, making 25th August a day of twin remembrance for Urdu lovers.

Why They Matter Today

In today’s world of authoritarian populism and rising inequality, their voices echo louder than ever. Makhdoom’s fiery call for justice, and Faraz’s lyrical defiance against dictators, remind us that poetry is not retreat but engagement.

Faraz once captured this spirit with wry irony:

“Bandagi hum ne chhod di hai, Faraz,

Kya karein log jab khuda ho jaayein.”

I have abandoned servitude, Faraz,

For what can one do when men become gods?

It is a line as relevant in today’s South Asia as when he first wrote it.

Twin Flames Still Burning

Separated by geography and generation, Makhdoom Mohiuddin and Ahmad Faraz nonetheless spoke to the same truths: that love without justice is hollow, and revolution without tenderness is barren.

On 25th August, when we remember both, we honour not only two poets but an entire tradition of Urdu poetry that refuses to choose between beauty and bravery. Their legacy insists that the truest verse is one that comforts the lover and emboldens the rebel—often in the same line.

Their dawns may have ended in 1969 and 2008, but the red glow of Makhdoom’s Surkh Savera and the lyrical rebellion of Faraz’s ghazals continue to light our nights.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai