The ten-day long Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav (Public Ganapati Festival) is Starting today with Ganesh Chaturthi, this festival will conclude ten days later on Ananth Chaturdashi, the last day of immersion.

Ganeshotsav or Ganapati festival is the most popular festival in Maharashtra and of late it is celebrated with pomp and grandeur in many other parts of India.

Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav: From Nationalist Revival to Modern Cultural Spectacle

As the ten-day long Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav (Public Ganapati Festival) approaches, commencing on Wednesday, August 27, 2025, with Ganesh Chaturthi and culminating on Ananth Chaturdashi, Maharashtra and parts of India brace for a vibrant explosion of devotion, music, and community spirit. This festival, honoring Lord Ganesha—the elephant-headed deity revered as the remover of obstacles—has transcended its religious roots to become a cornerstone of social, cultural, and political life. Once a modest family affair, it evolved into a grand public celebration in the late 19th century, thanks to the visionary efforts of Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak. Today, amid environmental challenges and political endorsements, Ganeshotsav continues to adapt, reflecting India’s dynamic societal fabric.

The Origins of the Cult of Ganesh

The worship of Lord Ganesha, or the “Cult of Ganesh,” finds its roots in ancient Hindu mythology and scriptures. According to legend, Ganesha was created by Goddess Parvati from the mud or turmeric paste of her body while she bathed, tasked with guarding her privacy. When Lord Shiva returned and was denied entry, a fierce battle ensued, resulting in Ganesha’s decapitation. To appease Parvati, Shiva replaced his head with that of an elephant, thus birthing the deity symbolizing wisdom, intellect, and new beginnings. This story, detailed in texts like the Puranas, underscores Ganesha’s role as Vighnaharta (remover of obstacles) and the patron of arts and sciences.

Historically, Ganesha’s veneration dates back to the Gupta Empire (4th-6th century CE), where early icons and temples emerged, portraying him as a benevolent figure in Buddhist and Jain contexts as well. By the medieval period (7th-15th century CE), his worship spread across regions, influenced by Bhakti movements that emphasized personal devotion. In Maharashtra, the festival gained prominence under the Maratha ruler Chhatrapati Shivaji in the 17th century, who promoted it to foster cultural nationalism and unity among Hindus. The Peshwas, Shivaji’s successors, elevated it to a state-sponsored event, with grand processions and idol immersions in rivers symbolizing the cycle of creation and dissolution.

However, with the decline of Maratha power and the rise of British colonialism in the 19th century, Ganesh Chaturthi retreated into private homes, losing its communal vibrancy. It was during this era of subjugation that the festival’s modern evolution began, transforming it from a domestic ritual into a powerful tool for social and political mobilization.

Lokmanya Tilak’s Revival: A Political Masterstroke in 1893

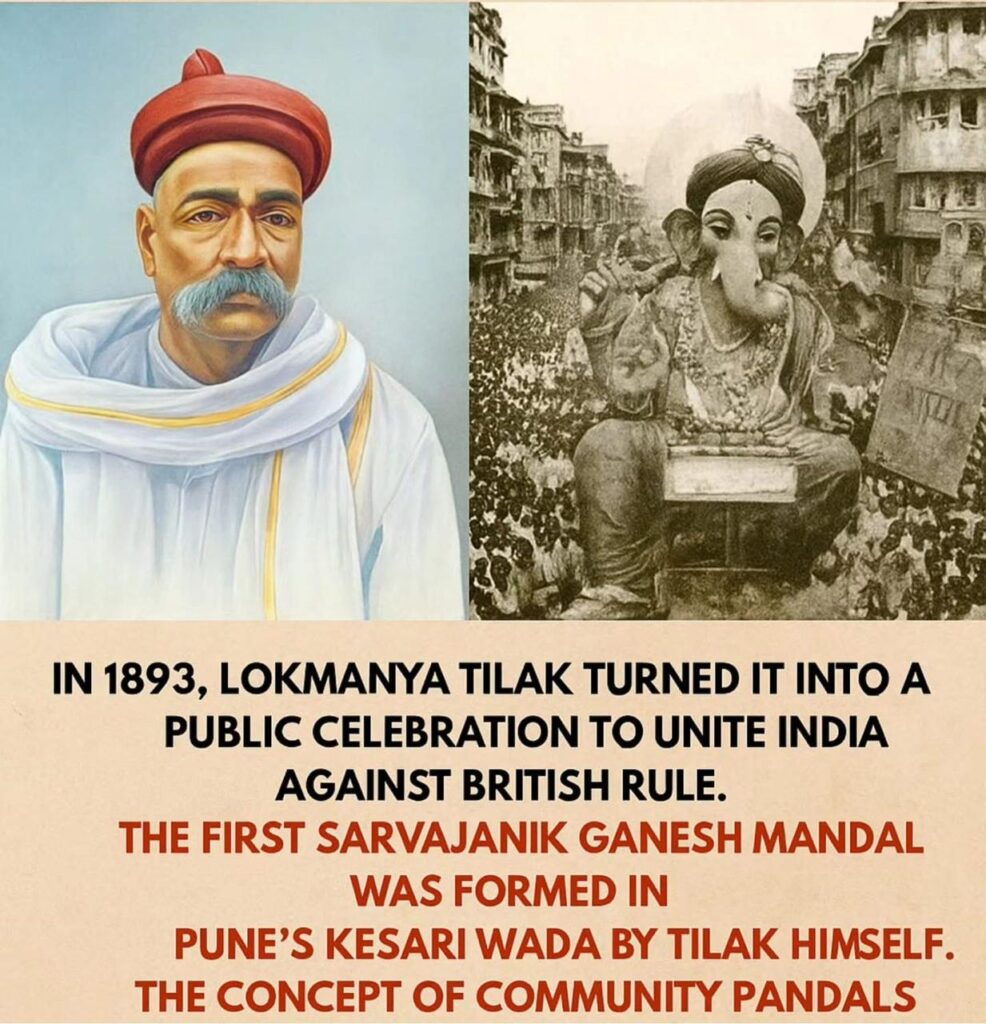

The pivotal moment in Ganeshotsav’s history arrived in 1893, when freedom fighter Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak reimagined the festival as Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav—a public celebration accessible to all. Tilak, a Chitpawan Brahmin and ardent nationalist, was inspired by communal tensions following Hindu-Muslim riots in Bombay (now Mumbai) that year. He saw an opportunity to unite Hindus across caste lines, countering British divide-and-rule policies that exacerbated religious divisions.

Tilak praised the efforts of early organizers like Bhausaheb Laxman Javale in his newspaper Kesari, advocating for community idols installed in pandals (temporary structures) where people could gather for prayers, lectures, and cultural programs.

The first public Ganeshotsav was held in Pune, with Tilak installing an idol at his Kesari Wada residence.

This shift from private (gharacha Ganpati) to public worship was revolutionary, as it bridged gaps between Brahmins and non-Brahmins, fostering a sense of shared identity.

Politically, the festival became a covert platform for anti-colonial discourse. Under the guise of religious gatherings, nationalists delivered speeches on swaraj (self-rule), boycotts of British goods, and cultural revival. Tilak’s strategy mirrored his broader efforts, including the Shivaji Jayanti festival, to instill pride and resistance.

By 1894, the British administration grew wary, imposing restrictions, but the movement had already spread to Mumbai and beyond, galvanizing the independence struggle.

Evolution Through the 20th Century: From Freedom Tool to Cultural Phenomenon

Post-Tilak, Ganeshotsav evolved rapidly, embedding itself in India’s freedom movement. In the early 20th century, mandals (community organizations) proliferated, organizing processions with patriotic songs, dances, and tableaux depicting historical events.

Leaders like Mahatma Gandhi acknowledged its unifying potential, though some critics noted its role in heightening communal tensions.

After India’s independence in 1947, the festival shed its overt political edge but retained its social significance. It spread to other states like Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, adapting local flavors—such as Karnataka’s emphasis on eco-friendly practices early on.

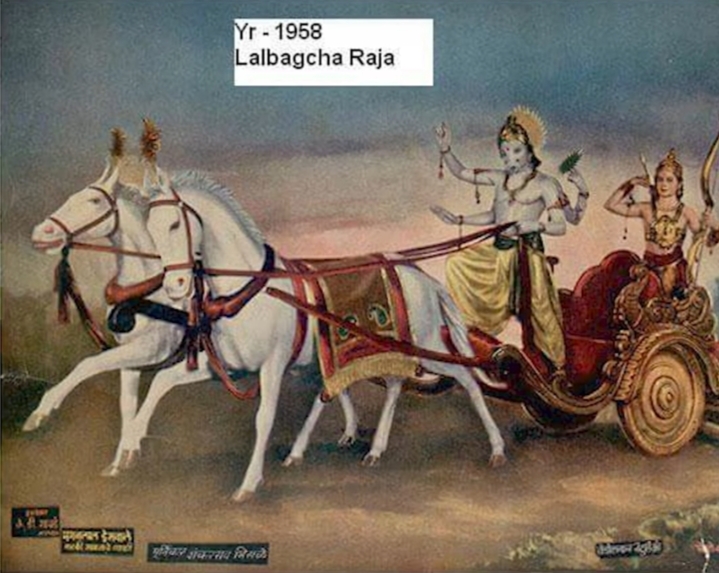

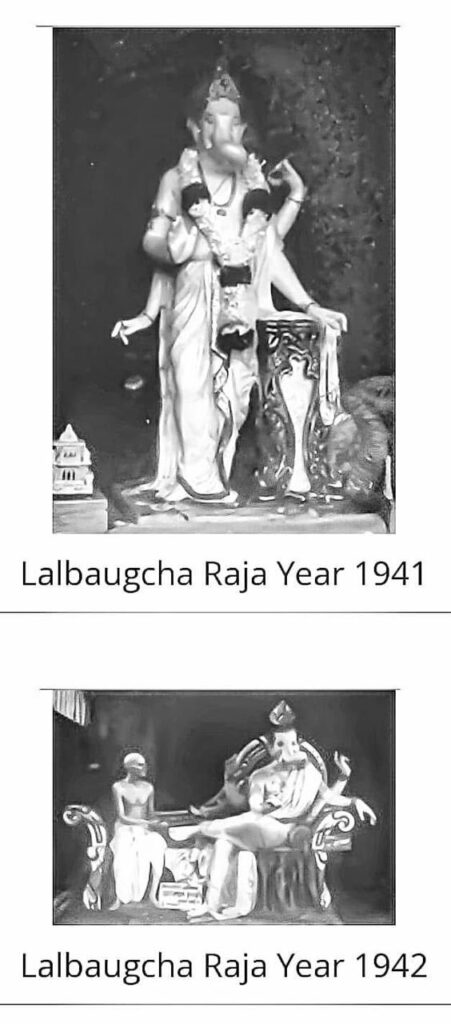

In Maharashtra, Mumbai’s Lalbaugcha Raja mandal, established in 1934, became iconic, drawing millions for darshan (viewing).

The mid-20th century saw commercialization creep in, with larger idols, amplified music, and sponsorships. Culturally, it became a showcase for arts: aarti (ritual prayers) accompanied by dhol-tasha drums, lavani dances, and modak (sweet dumplings) feasts symbolizing prosperity. Socially, it promoted inclusivity, with mandals organizing blood donation drives, health camps, and educational programs, reinforcing community bonds.

By the late 20th century, globalization influenced celebrations. Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) exported the festival to the USA, UK, and Australia, where it blended with local customs—virtual pujas during the COVID-19 pandemic in the 2020s exemplified this adaptability.

Contemporary Significance: Religious Devotion Meets Modern Challenges

In the 2020s, Ganeshotsav’s religious significance remains paramount. Devotees install idols at home or in pandals for 1.5 to 10 days, performing daily pujas, offering 21 types of leaves and flowers, and chanting mantras like “Ganpati Bappa Morya.” The immersion (visarjan) on Ananth Chaturdashi represents life’s impermanence, with cries of “Pudhchya Varshi Lavkar Ya” (come early next year) echoing hope.

Socially, it fosters harmony, transcending class and caste. Mandals like Pune’s Dagdusheth Halwai Ganpati, founded in the late 19th century, emphasize charity, feeding thousands and supporting education. Culturally, it’s a carnival of creativity: themed pandals depict social issues, from climate change to women’s empowerment, with Bollywood influences in dances and music.

Politically, the festival retains relevance. In July 2025, the Maharashtra government declared Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav a “state festival” (Rajya Utsav), allocating funds for global promotion and emphasizing its roots in nationalism and social unity. Critics, however, argue this move by the BJP-led coalition is a calculated bid to consolidate Hindu votes ahead of elections, echoing Tilak’s era but with contemporary electoral motives.

Environmental and Future Trajectories in the 2020s

A pressing modern challenge is environmental impact. Traditional plaster-of-Paris (PoP) idols, painted with toxic chemicals, pollute water bodies during immersion, harming marine life and causing sedimentation. In the 2020s, a green shift has gained momentum: eco-friendly clay idols, seed-embedded figures that sprout plants post-immersion, and artificial ponds for visarjan. Brands like those offering biodegradable materials report 45% annual growth, with artisans adapting to sustainable practices for livelihoods.

Regulations, such as bans on PoP in states like Maharashtra and court-mandated guidelines, reflect this awareness.

Yet, challenges persist: noise pollution from loudspeakers and plastic waste from decorations generate tons of debris annually.

Looking ahead, Ganeshotsav’s evolution suggests a balance between tradition and sustainability. As India navigates urbanization and climate crises, the festival’s core—unity and renewal—endures. In 2025, with Maharashtra’s state endorsement, it may amplify cultural tourism, but its true essence lies in Tilak’s vision: a celebration that empowers the masses.

This year’s festivities, starting August 27, promise innovation amid reverence, reminding us that Lord Ganesha not only removes obstacles but inspires adaptation. As pandals rise and drums beat, Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav reaffirms its role as a living tapestry of India’s heritage.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai