On the eve of the CWC meeting in Patna, the past echoes of Congress sessions in Bihar remind us of their enduring significance in India’s political journey.

Bihar’s Historic Role in the Congress Story

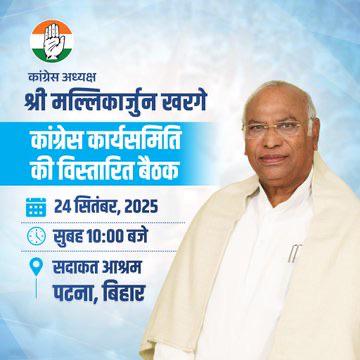

When the Congress Working Committee (CWC) gathers in Patna on 24 September 2025, it will not merely be another high-level political meeting. It will be a return to a soil that has, more than once, witnessed moments of historic consequence in India’s national movement. From the 27th Congress Session at Bankipore (Patna) in 1912, through the 37th Session at Gaya in 1922, to the 53rd Session at Ramgarh in 1940, Bihar has repeatedly provided the stage where the Congress debated, divided, and often decided its strategy against colonial rule.

Today, as Rahul Gandhi’s ‘Vote Adhikar Yatra’ galvanizes public discourse ahead of the Bihar assembly elections, the Congress’ choice of Patna for its CWC meeting is deeply symbolic. It is an invocation of a historical continuum where the struggles of the past meet the challenges of the present.

“Already a Great and Powerful Party of Liberal Muslims Had Arisen”

The Bankipore Session, Patna (1912)

The 27th Session of the Indian National Congress held at Bankipore in Patna in December 1912 was a landmark in more ways than one. Presided over by R.N. Modholkar, the session carried forward the Congress’ demand for greater representation and autonomy. Delegates pressed for:

•An elected majority in both the Imperial and Provincial Councils.

•An executive council for Punjab.

•Opposition to the extension of separate electorates to local bodies.

Interestingly, the session also reflected the limitations of the moderate phase. It controversially resolved that individuals ignorant of English should not be eligible for membership of local bodies—an indicator of the elite character of the early Congress.

What stood out, however, was the role of Mazhar-ul-Haq, the Reception Committee Chairman and a prominent nationalist from Bihar. In his address, he declared: “Already a great and powerful party of liberal Muslims had arisen whose aims and ideals were the same as those of the Congress.”

This articulation of Muslim participation in the national movement was crucial in bridging communal divides during a period of political uncertainty following the Morley-Minto Reforms (1909).

Bankipore thus symbolized both the aspirations and contradictions of the Congress in its formative years—seeking inclusivity while still carrying elitist imprints.

“Council Entry or Boycott?”

The Gaya Session (1922)

By the time the 37th Session convened in Gaya (December 1922), Indian politics had transformed. The Non-Cooperation Movement launched by Gandhi in 1920 had electrified the masses, but its abrupt suspension after the Chauri Chaura incident (1922) left the Congress divided on strategy.

Presided over by Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das, the Gaya session was dominated by a debate on Council Entry. Two distinct camps emerged:

•The No-Changers, led by C. Rajagopalachari and Gandhi, who insisted on continuing the boycott of colonial legislatures.

•The Swarajists, led by Das and Motilal Nehru, who argued for entering councils to obstruct colonial policies from within.

The session also saw participation from Rajendra Prasad—then an emerging leader from Bihar—who aligned with the No-Changers, foreshadowing his long association with Gandhian politics.

The Jamiat-ul-Ulema’s fatwa declaring council entry as “mamnoon” (permissible) but not “haram” (forbidden) added another dimension, reflecting the complexities of religious authority in nationalist politics.

The resolution, carried by a large majority, upheld the boycott of councils. Das resigned in protest, and the Swarajist-Congress split was formally underway.

The Gaya session thus exemplified the Congress’ inner struggles: should it persist with mass civil disobedience or adapt by using colonial institutions for nationalist purposes? These debates not only shaped the 1920s but also deepened Congress’ democratic culture of open contestation.

“India Will Not Fight for Imperial Interests”

The Ramgarh Session (1940)

If Bankipore symbolized early aspirations and Gaya reflected internal divisions, the Ramgarh Session (March 1940) represented a turning point under the shadow of the Second World War.

Presided over by Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, and organized with meticulous detail by Rajendra Prasad and Acharya J.B. Kripalani, the session confronted the question of India’s involvement in Britain’s war effort.

The Congress unequivocally declared that India could not support Britain’s war unless independence was guaranteed. The resolution demanded:

•An immediate declaration of India’s freedom.

•A democratic Indian government empowered to decide its war policy.

The session was disrupted by torrential rain, but not before the Congress made clear that Indian participation in the war would not be unconditional. This stance brought the party into sharp conflict with the British, paving the way for the Quit India Movement (1942).

The Ramgarh session also underscored the role of Bihar’s leadership—Rajendra Prasad, then emerging as one of Gandhi’s closest associates, played a vital role in organizing the massive congregation of over 15,000 delegates and volunteers.

The Congress Working Committee: From Nagpur (1920) to Patna (2025)

The Congress Working Committee (CWC) itself, first institutionalized at the Nagpur Session in 1920, became the nerve centre of Congress politics. From leading negotiations with the British to steering mass movements, the CWC shaped the trajectory of the freedom struggle.

In independent India too, the CWC has remained the Congress’ highest decision-making body. When it convenes in Patna this week, it will be doing so in a state where its history runs deep.

Bihar as a Congress Battleground

Bihar has not just hosted historic sessions; it has produced some of the tallest Congress leaders—Rajendra Prasad, the first President of India; Anugrah Narayan Sinha, a pioneer in agrarian reforms; and Mazhar-ul-Haq, an early nationalist bridge-builder.

Yet, post-independence, Bihar also became a theatre of the Congress’ decline. The rise of socialist politics under Jayaprakash Narayan and later the regional dominance of leaders like Lalu Prasad Yadav and Nitish Kumar pushed the Congress to the margins.

The 2025 CWC meeting in Patna comes, therefore, with dual symbolic weight: it recalls Congress’ historic centrality in Bihar while confronting its contemporary marginality in the state’s politics.

Rahul Gandhi’s Yatra and the Electoral Road Ahead

Rahul Gandhi’s ‘Vote Adhikar Yatra’, cutting across caste and class lines, is aimed at reviving the Congress’ connect with Bihar’s grassroots ahead of the assembly elections. By timing the CWC meeting in Patna, the party signals that it sees Bihar not just as an electoral battleground but as a moral-political landscape where its legacy still resonates.

If Bankipore showcased liberal Muslim participation, if Gaya highlighted democratic debate, and if Ramgarh underlined uncompromising nationalism, the 2025 Patna CWC may seek to project a revived Congress unity and commitment to constitutional democracy in the face of present-day challenges.

Echoes of the Past, Demands of the Present

As the Congress Working Committee sits in Patna this week, it does so against a backdrop both historic and contemporary. Bihar’s tryst with Congress sessions is not merely a matter of nostalgia—it is a reminder of the inclusive, contested, and principled politics that once defined the party.

From Mazhar-ul-Haq’s assertion of Hindu-Muslim unity at Bankipore to Azad’s defiant nationalism at Ramgarh, Bihar has witnessed Congress at its best moments of clarity and courage. Whether the Patna meeting of 2025 can reclaim even a fraction of that spirit remains to be seen.

But one thing is certain: in the history of India’s freedom movement, Bihar was never a bystander. It was a stage, often the centre, where the Congress rehearsed and redefined the script of the nation’s destiny.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai

~Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai