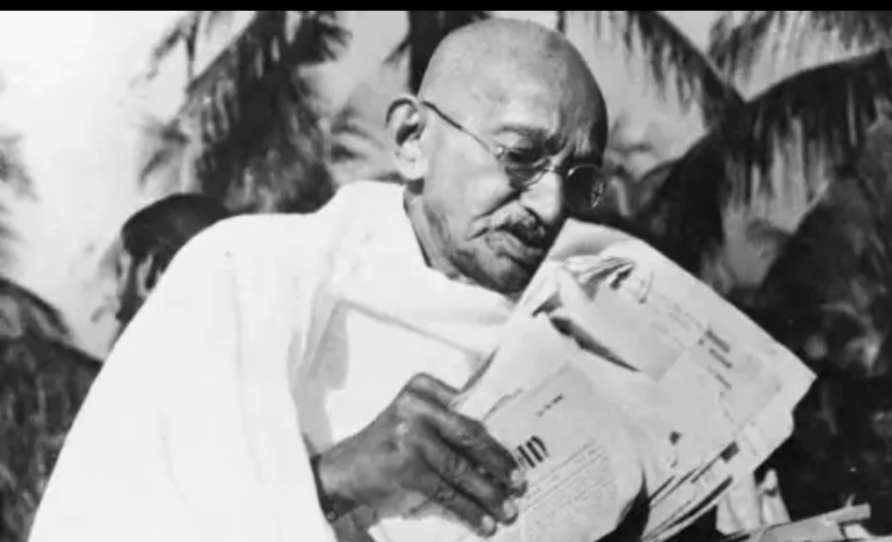

October 2, 2025, marks a confluence of milestones: the 156th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, celebrated as Gandhi Jayanti; the festival of Vijayadashami, symbolizing the triumph of good over evil; and the 100th Foundation Day of the Rastriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Yet, this alignment carries a profound irony. Gandhi’s vision of an “Inclusive Hinduism,” grounded in Sarva Dharma Sambhav—equal respect for all religions—stood as a bulwark against the “exclusive Hindutva” of the RSS, which emphasizes cultural homogeneity and majoritarian claims.

As India reflects on these overlapping commemorations, the day underscores the enduring tension between unity through pluralism and nationalism defined by exclusion. Gandhi’s ethical interpretation of Hinduism, centred on non-violence, truth, and respect across faiths, challenged divisive ideologies.

At a time of resurgent polarization, his approach remains a vital guide for preserving pluralism.

Ahimsa: The Core of Gandhi’s Hinduism

Gandhi’s Hinduism was not rigid doctrine but a dynamic pursuit of truth, which he equated with divinity. Drawing on the Vedas and Upanishads, he embraced their ethical teachings while discarding elements that clashed with reason. Influenced by reformers like Tulsidas, he emphasized compassion, universal brotherhood, and mercy over dogma.

To him, the highest expression of Hinduism was ahimsa (non-violence) and self-purification, not triumphalist civilizational claims. Religion, he insisted, should soften politics, not weaponize it.

Sarva Dharma Sambhav: Respect Across Faiths

Sarva Dharma Sambhav became a cornerstone of Gandhi’s philosophy: all religions, he argued, lead to the same divine truth. His Experiments with Truth and Eleven Vows—non-violence, tolerance, respect for all faiths—reflected a commitment to multiculturalism.

This ethic shaped everyday politics. His outreach to Muslims during the Khilafat-Congress alliance, his insistence on temple and mosque visits by leaders, and his rebukes of communal provocations embodied interfaith solidarity. His vocabulary of satya (truth) and sacrifice made exclusionary nationalism difficult to reconcile with his moral leadership.

The Rise of Hindutva

During the freedom struggle, Gandhi faced communal ideologies that defined the nation narrowly through a Hindu identity. Leaders of this movement advocated a “Hindu Rashtra,” often marginalizing minorities. Their vision, rooted in exclusion and inspired partly by authoritarian models, stood in stark contrast to Gandhi’s pluralism.

Vinayak Savarkar’s Hindutva defined nationhood as a civilizational category, with India ideally shaped by Hindu norms. The RSS, founded in 1925 by K. B. Hedgewar, built disciplined cadres through shakhas to consolidate Hindu society. Its worldview privileged cultural homogeneity, treated minorities with suspicion, and translated grievance into a mass majoritarian project.

Swaraj as Shared Struggle

Gandhi integrated Hindu-Muslim unity into his campaigns, such as the Khilafat Movement, directly challenging narratives of inherent conflict. His mass mobilizations—Non-Cooperation (1920–22) and the Salt March (1930)—brought Hindus, Muslims, and others under Swaraj as a shared spiritual and political quest.

Amid rising communal violence in the 1940s, he undertook fasts, including in Calcutta in 1947, to quell riots and appeal to shared humanity. He opposed partition, warning it would fracture India’s fabric, and denounced those who mobilized hatred in religion’s name.

Truth Versus Discipline

Gandhi’s strategy blended moral persuasion with collective action. His fight against untouchability, fasts during riots, and insistence on interfaith recognition all deepened his authority across communities.

Unlike Hindutva’s emphasis on force and discipline, Gandhi championed moral equality, dignity through non-violence, and civic solidarity. He sought not only to critique Hindutva but to address its roots in social discontent through rural uplift, caste reform, and constructive programmes.

Gandhi’s Hinduism as Counterweight

Gandhi’s religious ethic countered exclusionary nationalism in multiple ways:

•Citizenship as equality, not conformity: He insisted faith must not determine rights.

•Rejecting humiliation and revenge: While Hindutva mobilized grievance, Gandhi offered dignity through self-discipline.

•Cross-community practices: His constructive programmes created solidarities across caste and creed.

•Rebuttal of homogenizing history: He emphasized India’s plural past and moral continuities across traditions.

Legacy and Relevance

Yet Gandhi’s moral counterweight was not decisive. Hindutva built enduring institutions—schools, volunteer networks, political wings—that outlived his assassination in 1948. His ethic, rooted in personal example, was difficult to institutionalize.

Still, Gandhi’s ideas shaped India’s secular Constitution, enshrining equal respect for all religions. His legacy left behind a moral vocabulary against communalism that critics of majoritarianism continue to invoke.

In today’s India, where polarization and cultural nationalism are resurgent, Gandhi’s philosophy offers an antidote. His call for universal brotherhood, rooted in spiritual convergence, challenges narratives privileging one community. Attempts to selectively co-opt Gandhi’s legacy only highlight the tension between his pluralist vision and exclusionary projects.

The Contest That Defines India

India again stands at a crossroads. By embracing Gandhi’s inclusive Hinduism and rejecting exclusionary nationalism, the nation can honour his legacy and reaffirm its commitment to pluralism. Where Hindutva offers cultural primacy and organizational discipline, Gandhi offers a politics of moral appeal and inclusive citizenship.

The contest between these visions—ahimsa versus force, Sarva Dharma Sambhav versus exclusion, Swaraj as shared struggle versus sectarian triumphalism—continues to define India’s modern trajectory.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai