“ab ke ham bichhḌe to shāyad kabhī ḳhvāboñ meñ mileñ”“If we part now, perhaps we will meet again in dreams.”

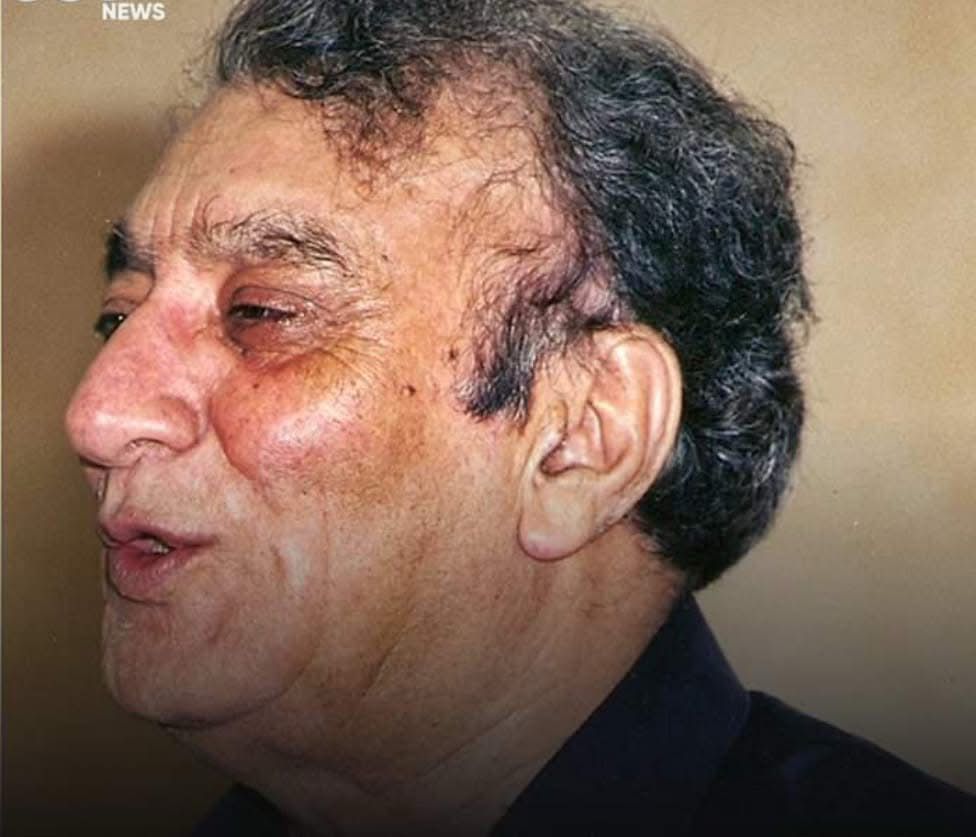

On 12 January 2026, the Urdu-speaking world marks the 95th birth anniversary of Ahmad Faraz, the poet who made love sound like defiance and resistance feel like tenderness. Nearly two decades after his passing, Faraz still lives in our collective memory as the rare poet who could make a whispered ghazal echo like a political slogan — and a protest feel like a lover’s lament.

Born Syed Ahmad Shah in 1931, Faraz belonged to that luminous generation of Urdu poets who wrote not just for literary salons but for streets, prisons, exile and the wounded heart of South Asia. His pen name ‘Faraz’ soon became synonymous with lyrical rebellion — a voice that refused to bow before power, orthodoxy or cruelty.

“bandagī ham ne chhoḌ dī hai ‘farāz’ / kyā kareñ log jab ḳhudā ho jaa.eñ”

“I have given up worship, Faraz — what can one do when people themselves become gods?”

Faraz was never content to be merely a romantic poet. In a country repeatedly scarred by military coups and authoritarian rule, he stood among those who spoke truth to power, even when the price was exile, censorship and institutional punishment.

As a poet who openly criticised dictatorships in Pakistan, Faraz was pushed out of official life, sidelined and at times forced abroad. Yet he refused to soften his voice. His verses kept naming arrogance, tyranny and moral hypocrisy — not in the dry language of manifestos, but through irony, wit and piercing lyricism.

It is this union of politics and poetry that made Faraz unique: he did not shout slogans; he turned dissent into music.

“rānjish hī sahī, dil ko dukhāne ke liye ā”

“Come, even if it is only to wound my heart.”

Yet Faraz’s genius lay in his ability to move effortlessly between the political and the personal. Few poets have written of love with such aching vulnerability. His ghazals speak of longing, separation, wounded pride and the strange dignity of heartbreak — themes that found immortal voice through legends like Mehdi Hassan, Noor Jehan, Ghulam Ali, Jagjit Singh, Pankaj Udhas and Runa Laila.

When Mehdi Hassan sang Faraz’s lines, they travelled beyond Pakistan into India, across languages and borders, becoming part of a shared subcontinental emotional vocabulary. Lovers who had never heard of military dictators or literary movements still knew Faraz — because they had wept to his couplets.

“kuchh to mere pindār-e-mohabbat kā bharam rakh”

“At least preserve the dignity of my love.”

Faraz’s language was deceptively simple. Beneath the elegance lay an extraordinary economy of words — a craft that could compress philosophy into a single couplet. His poetry did not overwhelm with ornamentation; it disarmed with clarity.

Collections such as Pas-e-Andaaz, Sab Awaazein Meri, Khwaab-e-Gul, Janaan Janaan and Ghazal Bahaana Karoon established him as one of the most influential modern Urdu poets of the twentieth century — a writer who could speak to both the elite critic and the ordinary reader.

Even when he held prestigious posts — including heading national literary institutions — Faraz remained, at heart, a rebel poet. His allegiance was always with the vulnerable, the marginalised, the emotionally bruised.

“ab tak dil-e-khush-fahm ko tujh se haiñ ummīdeñ”

“Even now, this naive heart still hopes for you.”

Perhaps this is why Faraz still feels contemporary. In an age of rising intolerance, shrinking freedoms and cultural polarisation, his verses remind us that poetry can be both beautiful and brave. He taught us that to love deeply is itself a political act — a refusal to become cruel, cynical or numb.

Ahmad Faraz died on 25 August 2008, but his poetry never left. It circulates in ghazal mehfils, on old cassettes, in digital playlists, in whispered couplets between lovers, and in the private rebellions of readers who still believe words can challenge power.

On his 95th birth anniversary, Faraz stands not as a relic of the past, but as a living presence — a poet who continues to speak to the anxieties, passions and defiance of our own fractured times.

And somewhere between love and resistance, between grief and hope, his voice still says:

“ab ke ham bichhḌe to shāyad kabhī ḳhvāboñ meñ mileñ.”

If we part now, perhaps we will meet again in dreams.

~Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai