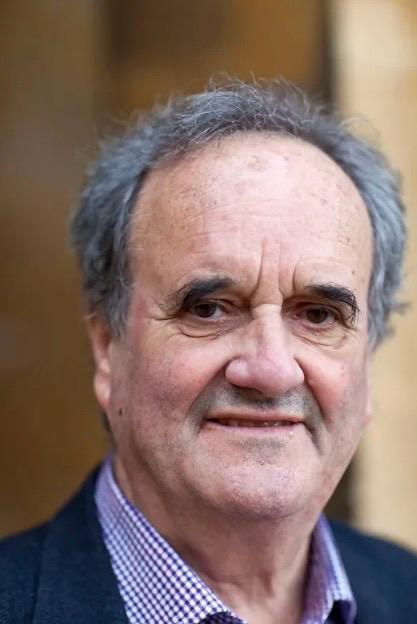

On January 25, 2026, a profound silence descended upon Delhi. It was as if the city, usually a cacophony of ambition and struggle, had deliberately muted its voice. The departure of Sir William Mark Tully feels like the sudden disappearance of a familiar frequency—a quietness that demands reflection. Yet, to say Tully is “no more” is an incomplete sentence. The truth is that Mark Tully transcended the transient world of “breaking news” decades ago, on that day in July 1994 when he resigned from the BBC in utter disillusionment. At that moment of professional ending, he was spiritually reborn.

His passing is not a headline; it is a pause. It is the very pause he introduced into his own life long ago. As he famously chronicled in *No Full Stops in India*, this country does not permit finality. His death, too, is like an unfinished sentence that will continue to echo in the collective memory of the subcontinent.

The Soul vs. The Monolith

The roots of Tully’s legendary status lay in his unwavering moral compass. He famously sparred with the BBC of the John Birt era—a time when “management” became a language of fear and secrecy. For Tully, this was anathema. He belonged to a school of journalism where questioning was more sacred than obedience.

He warned that the BBC was becoming a “secret monolith” where ratings were worshipped and the soul was exiled. This “exile of the soul” began at the pinnacle of journalistic excellence, and today, we see the consequences: soulless bodies of media outlets across the globe that have become little more than ghosts of their former selves. His resignation held no drama, only a profound moral weariness. It was the moment a writer left his desk to reclaim his pen.

A Native Distanced, A Stranger Embraced

Even after the microphone was switched off, Tully remained a Voice. India was never a mere “posting” for him; it was a memory stretching back to his childhood in Tollygunge and the boarding schools of Darjeeling. It remains an irony of history that the very country from which he was socially distanced during his British education was the one that embraced him most closely.

He often expressed a unique, poignant pain: “It’s a great shame for this country that when I speak in Hindi, people reply in English.” This wasn’t a linguistic complaint; it was the ache of a man who had learned India not through grammar, but through feeling.

Witness to the Cracks in Civilization

Tully viewed India not as a series of events, but as a slow, unfolding process. To him, the Bhopal gas tragedy, Operation Blue Star, the assassination of Indira Gandhi, and the demolition of the Babri Masjid were not just stories—they were cracks in the fabric of civilization.

In 1992, as a mob in Ayodhya chanted “Death to Mark Tully,” he was locked in a room—not just physically, but within an India that was beginning to close itself off. He later described the fall of the Babri Masjid as the greatest defeat of independent India’s secular dream. It was an elegy, not an analysis. It is a sobering reflection of our times that what Tully mourned as a defeat, contemporary journalism often presents as a triumph.

The Philosophy of Slow Motion

After 1994, Tully chose Delhi over London, the village over the studio, and the train over the flight. His philosophy was simple: India cannot be understood in a hurry. In works like India in Slow Motion, he breathed life into the mundane.

His life was punctuated by the unique humour of Indian politics. He recalled his friend, the grassroots leader Chaudhary Devi Lal, admitting during an election, “I’m very bored.” When Tully pointed out that the manifesto was good, Devi Lal laughed: “Fool, I haven’t read a single manifesto… but every man in the village knows me.” Tully saw this as the most accurate definition of democracy.

Beyond the Newsroom: Cricket, Cinema, and Souls

Tully’s interests were as vast as the country he inhabited. He was a devoted supporter of Indian cricket, recognizing the spark in a young Mahendra Singh Dhoni at first sight—not as an analyst, but as a storyteller who could read character. He held a deep affection for Rajiv Gandhi, believing that had he not been assassinated, India would be far ahead.

His love for Hindi cinema—from Naya Daur to Omkara—was almost familial. He admired actors like Amrish Puri and Naseeruddin Shah for their “souls.” He once joked that upon receiving his knighthood, his only unfulfilled dream was to play a small role in a film alongside Amrish Puri. Sadly, Puri passed away shortly after they spoke, leaving that dream, like so many of Tully’s wishes, beautifully incomplete.

The Man Who Lived India

Mark Tully was often called “a foreigner who understood India.” This description does him a grave injustice. He didn’t just understand India; he lived it. Understanding requires distance; living requires risk.

In 1994, he left the BBC quietly. Today, in 2026, he has laid down his body just as simply, like a clean, folded sheet. To the world, he was a gentle giant of journalism and a master storyteller. To India, he was simply one of our own.

~Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai