Safar mein dhoop to hogi jo chal sako to chalo*

(The sun will scorch the journey—walk on, if you have the courage to walk.)

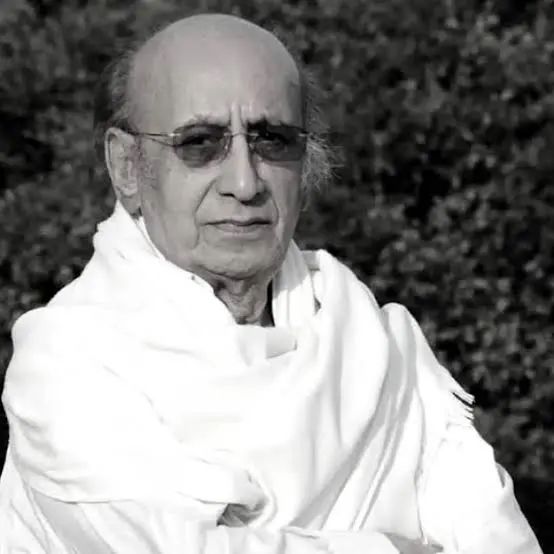

On his tenth death anniversary, 8 February, Nida Fazli’s voice continues to move through our fractured times like a stubborn beam of light. A poet who chose to stay back when history was tearing families apart, who preferred the idiom of the street over the ornament of the court, and who believed compassion to be a higher prayer than ritual, Fazli endures as one of the most humane and accessible voices of post-Independence Urdu poetry.

Born Muqtida Hasan Nida Fazli in Delhi on 12 October 1938 and raised in Gwalior, he inherited poetry from his father but shaped it in an idiom distinctly his own. In 1965, when his parents migrated to Pakistan nearly two decades after Partition, Fazli chose India. That decision—quiet yet momentous—became the emotional undercurrent of his life and literature. Separation, memory, displacement and an unyielding refusal to surrender to communal bitterness recur like muted refrains in his poetry.

*Kabhi kisi ko mukammal jahan nahin milta*

(No one ever receives a world complete.)

Few lines in modern Urdu poetry have travelled as widely as this couplet from Ahista Ahista (1981). In a society seduced by absolutes—perfect love, perfect faith, perfect nationhood—Fazli reminded us of the dignity of incompleteness. His realism was not cynical; it was compassionate. He accepted life’s fractures without glorifying despair.

His poetry avoided heavy Persianised diction and elaborate metaphors. Instead, he cultivated clarity—lucid, conversational, deceptively simple. Poetry, he believed, must breathe the air of lived experience. That is why his ghazals and nazms flowed easily from mushairas into drawing rooms, from literary journals into film songs, from classrooms into popular memory.

His collections—Lafzon Ka Pul, Mor Naach, Aankh Aur Khwaab Ke Darmiyan, Khoya Hua Sa Kuchh (which won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1998), and his collected Kulliyaat—chart an inner landscape of exile, urban loneliness and fragile hope. His prose works, including Mulaqatein and the autobiographical Deewaron Ke Beech (recipient of the Mir Taqi Mir Award), reveal a fiercely independent critic who did not hesitate to question even celebrated contemporaries.

*Ghar se masjid hai bahut door, chalo yoon kar lein / Kisi rote hue bachche ko hansaya jaaye*

(The mosque is far from home—come, instead / let us make a crying child smile.)

In these two lines lies an entire ethical manifesto. Fazli collapsed the distance between ritual and righteousness, suggesting that the purest devotion lies in easing human suffering. At a time when sectarian rhetoric often drowns out quieter moral voices, this couplet feels startlingly relevant.

Fazli witnessed the violence of his era firsthand. He spoke out against communal riots and fundamentalism; during the unrest of December 1992, he was compelled to seek refuge for safety. Yet he refused bitterness. His response to hatred was not counter-hatred but a deeper humanism—an ethos recognised when he received the National Harmony Award.

In contemporary India, still negotiating the uneasy terrain of pluralism and identity, his poetry reads not as nostalgia but as moral instruction.

*Duniya jise kehte hain jaadu ka khilauna hai / Mil jaaye to mitti hai, kho jaaye to sona hai*

(The world, they say, is a magical toy— / if you possess it, it is dust; if you lose it, it becomes gold.)

With characteristic irony, Fazli exposed the illusions of power and possession. Even as he wrote for cinema, he retained a poet’s detachment. He often described lyric-writing as a craft shaped by the compulsions of script and director, yet he infused popular songs with literary finesse.

From Tu is tarah se meri zindagi mein shaamil hai (Aap To Aise Na The, 1980) to Hosh walon ko khabar kya (Sarfarosh, 1999), from Tera hijr mera naseeb hai (Razia Sultan, 1983) to Aa bhi jaa (Sur, 2002), his lyrics married poetic depth with mass appeal. His collaboration with Jagjit Singh on Insight (1994) gave his ghazals a haunting musical afterlife. The Padma Shri in 2013 and several film awards acknowledged what audiences already knew: his words had entered the bloodstream of popular culture.

Yet beneath the accolades stood a poet who never forgot Gwalior’s bylanes or the trauma of a divided family. In his poetry, the modern city becomes both place and metaphor—crowded yet isolating, luminous yet suffocating.

*Yeh hai zindagi, kuchh khwaab chand umeedein / Inhi khilonon se tum bhi behal sako to chalo*

(This is life—some dreams, a few hopes; / if you can console yourself with these small toys, walk on.)

There is stoic tenderness in these lines. Fazli did not promise utopia; he offered endurance. He dignified fragility without romanticising suffering. In a literary culture often polarised between austere modernism and easy sentimentality, he carved out a third space—intimate yet public, critical yet compassionate.

He invoked Mir and Ghalib with reverence, yet remained rooted in the anxieties of his own time. Even in his later years, writing columns for BBC Hindi, he engaged with society with undiminished candour.

Nida Fazli passed away on 8 February 2016 in Mumbai. But poets of his stature do not disappear into memory. They persist in everyday speech, in a line recalled on a solitary evening, in a quiet act of kindness performed without applause.

In an age shadowed again by suspicion and hardening identities, his words feel less like verse and more like a moral compass.

*Safar mein dhoop to hogi jo chal sako to chalo*

(The journey will be harsh—walk on, if you have the courage.)

And perhaps that is his enduring gift: not consolation alone, but courage—the courage to remain human when the times tempt us otherwise.

~Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai

~Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai