The Book Ban in Kashmir: Censorship as a Threat to Democracy, Discourse, and Dissent

From Orwell to Arundhati Roy, from ancient emperors to modern governments—book banning has always served one goal: control. The recent ban on 25 books in Jammu and Kashmir marks a new low in India’s democratic and intellectual history.

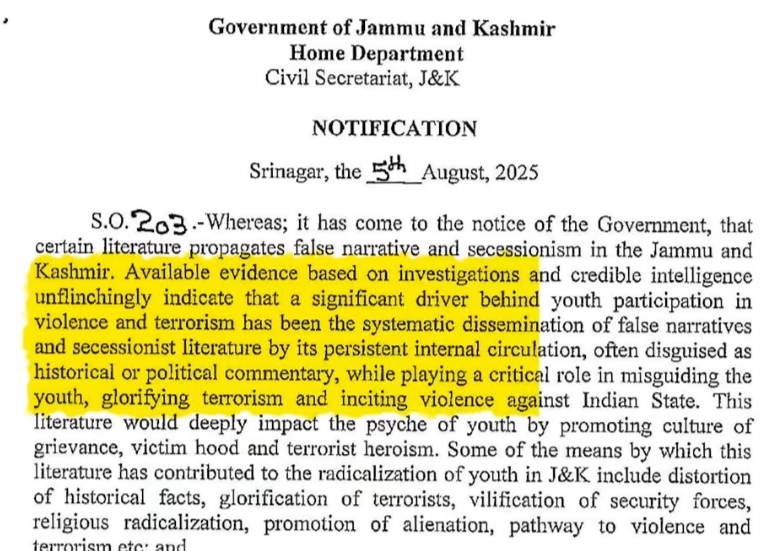

On August 5, 2025, the Government of Jammu and Kashmir issued a sweeping ban on 25 books, invoking the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) and the newly-enacted Bhartiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS). The official reasoning: these books purportedly spread “secessionist narratives” and “glorify terrorism.” But beneath the legalese lies a graver truth—this act is a direct assault on freedom of speech and expression, academic freedom, and the fundamental right of readers to think, question, and choose.

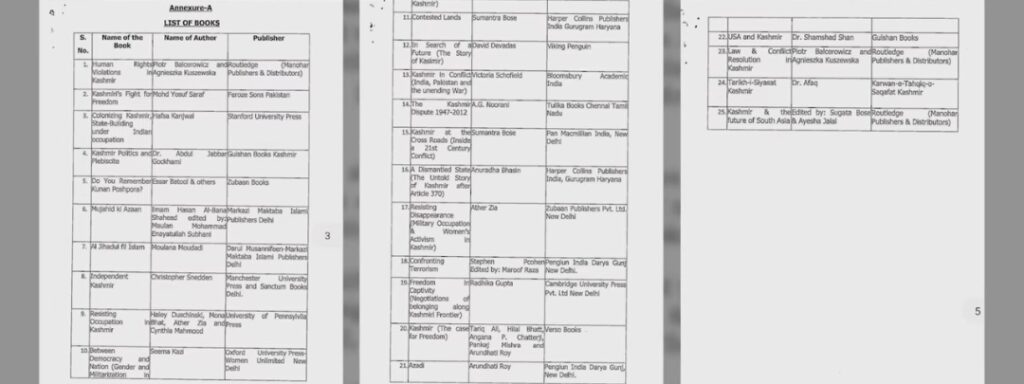

A Chilling List of Banned Voices

The list of banned books reads like a who’s who of global and Indian scholarship on Kashmir. From Arundhati Roy’s Azadi and A.G. Noorani’s The Kashmir Dispute (1947–2012), to Anuradha Bhasin’s A Dismantled State and Sumantra Bose’s Contested Lands, the ban affects voices that have long shaped public discourse and scholarly debate. Even conservative commentator Maroof Raza’s Confronting Terrorism makes the list—a deeply ironic inclusion that underlines the arbitrariness of the state’s logic.

More egregiously, David Devadas’s In Search of a Future: The Story of Kashmir—a widely respected, balanced, and dispassionate account of post-1947 Kashmir—has been lumped together with books the administration claims promote secessionism. One would be hard-pressed to find a more absurd example of bureaucratic overreach and intellectual illiteracy.

This isn’t just about a list of books. It’s about an attack on the very idea of free inquiry, critical reflection, and democratic dissent.

The Global and Historical Context of Book Bans

Book banning is not new. It has historically served as a tool for silencing voices, controlling historical narratives, and protecting authoritarian ideologies. From Emperor Shih Huang Ti of ancient China—who burned books to erase rival histories—to the Comstock Act of 1873 in the United States, and Nazi Germany’s bonfires of “un-German” literature, book bans are a familiar tactic of authoritarian regimes.

Famous literary works like Orwell’s Animal Farm, Huxley’s Brave New World, and Joyce’s Ulysses have been banned for their political critique, supposed obscenity, or ideological dissent. Maya Angelou, Angie Thomas, and Salman Rushdie have all faced the wrath of governments and school boards for writing truth to power.

In India too, the banning of Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses in 1988 set a precedent for mixing religious sensitivity with state censorship. Bans on books by Stanley Wolpert, V.S. Naipaul, and even Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s Riddles in Hinduism reveal how fragile Indian democracy becomes when forced to accommodate the insecurities of political power.

The Constitutional Farce

India’s Constitution, under Article 19(1)(a), guarantees the right to freedom of speech and expression. Exceptions do exist—such as concerns about public order, security of the state, and morality—but they are meant to be narrow, proportionate, and exceptional.

By invoking vague and sweeping charges like “glorifying terrorism” and “spreading secessionism,” the J&K administration not only violates constitutional protections but also undermines the reader’s right to receive information—a critical dimension of free speech affirmed by the Indian Supreme Court in multiple rulings.

Furthermore, the ban also violates international covenants India is a signatory to, including Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), both of which enshrine the freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds.

Academic Freedom Under Siege

Many of the banned books are scholarly works published by prestigious academic presses like Oxford University Press, Routledge, University of Pennsylvania Press, and Cambridge University Press. These are not fringe tracts or hate literature—they are peer-reviewed, footnoted, rigorously researched contributions to political science, sociology, history, and gender studies.

Banning these works is tantamount to criminalizing academic research. It also sends a chilling message to scholars worldwide: that any critical inquiry into Kashmir’s history, society, and politics risks being labeled “anti-national.”

This authoritarian impulse undermines academic freedom, one of the cornerstones of higher education and democratic societies. As UNESCO’s 1997 Recommendation on the Status of Higher-Education Teaching Personnel makes clear, academic freedom includes the right “to express freely their opinion about the institution or system in which they work, to fulfill their functions without discrimination or fear of repression.”

The Danger of a Slippery Slope

Once a government begins banning books in the name of national security, there is no logical stopping point. Today, it is books on Kashmir. Tomorrow, it could be books on caste, gender, communalism, or economic inequality. This slippery slope leads to a cultural landscape where only state-approved narratives survive, and dissenting voices are criminalized.

It is important to remember: censorship does not eliminate ideas—it merely drives them underground, giving them a mythic power and allure. In an age of digital connectivity, where most of these books are available as PDFs or e-books online, such bans are not only anti-democratic but also technologically futile.

The Irony of “Saving” Kashmir by Banning Its Histories

The administration claims that the banned books incite violence or mislead youth into “terrorism.” But reality suggests the opposite. It is the suppression of truth, the denial of justice, and the choking of democratic dialogue that radicalizes people.

A society cannot heal from its traumas without confronting them honestly. Books like Do You Remember Kunan Poshpora?—which documents sexual violence allegedly perpetrated by Indian forces—may be uncomfortable, but they are part of the historical record. Silencing them doesn’t erase what happened; it merely adds state complicity to the ledger of injustice.

Reactions: A Mixed Chorus of Condemnation

Scholars, journalists, and civil liberties groups have reacted with outrage. One prominent critic wrote:

“I may disagree with most of the books on the list, but I will never support banning literature. It’s moronic to ban books or any literature —especially in the age of the internet and free e-books.”

Another asked poignantly:

“Why has the government banned In Search of a Future by David Devadas, a book praised for its even-handed treatment of the Kashmir conflict, while allowing many actually incendiary tracts to circulate freely?”

Such selective bans only deepen the perception of bias and vendetta, especially in a region like Kashmir where trust in state institutions is already fragile.

The School Ban Circular: Symptom of a Wider Malaise

The same week, the Directorate of School Education, Kashmir issued a circular banning the sale of books and uniforms within private school premises. Ostensibly, the move was to curb profiteering by schools, but in context, it reflects the growing desire of the state to control educational ecosystems, dictate reading choices, and monitor intellectual inputs.

When the state decides which books children may or may not read, education ceases to be liberatory. It becomes another instrument of indoctrination.

What’s at Stake: Democracy Itself

A democracy is not just the act of voting every five years. It is a culture of dissent, debate, and dialogue. Book banning is not merely about a list of 25 titles—it is about eroding the very foundations of free thought.

We must ask ourselves: Who decides which ideas are dangerous? Who benefits from suppressing critical voices? And what kind of nation silences its own historians, novelists, and thinkers?

As citizens, educators, writers, and readers, we must assert that freedom of expression is not a privilege to be granted by the state. It is a non-negotiable right, enshrined in our Constitution and indispensable to our collective future.

Because when books are banned, it is not the books that are on trial. It is the society that bans them.

Postscript: Call to Resistance

The international community, civil rights organizations, universities, and publishing houses must not remain silent. Groups like PEN International, Amnesty International, and the United Nations Human Rights Council must speak out and condemn this growing censorship.

The Indian government must be reminded: banning books doesn’t ban truth. It only proves its fear of it.

Let us read what they don’t want us to read. Let us preserve what they want to erase. Because in the end, truth survives. It always does.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai. He writes on history, culture, politics, religion, memory, and pluralism in South Asia.