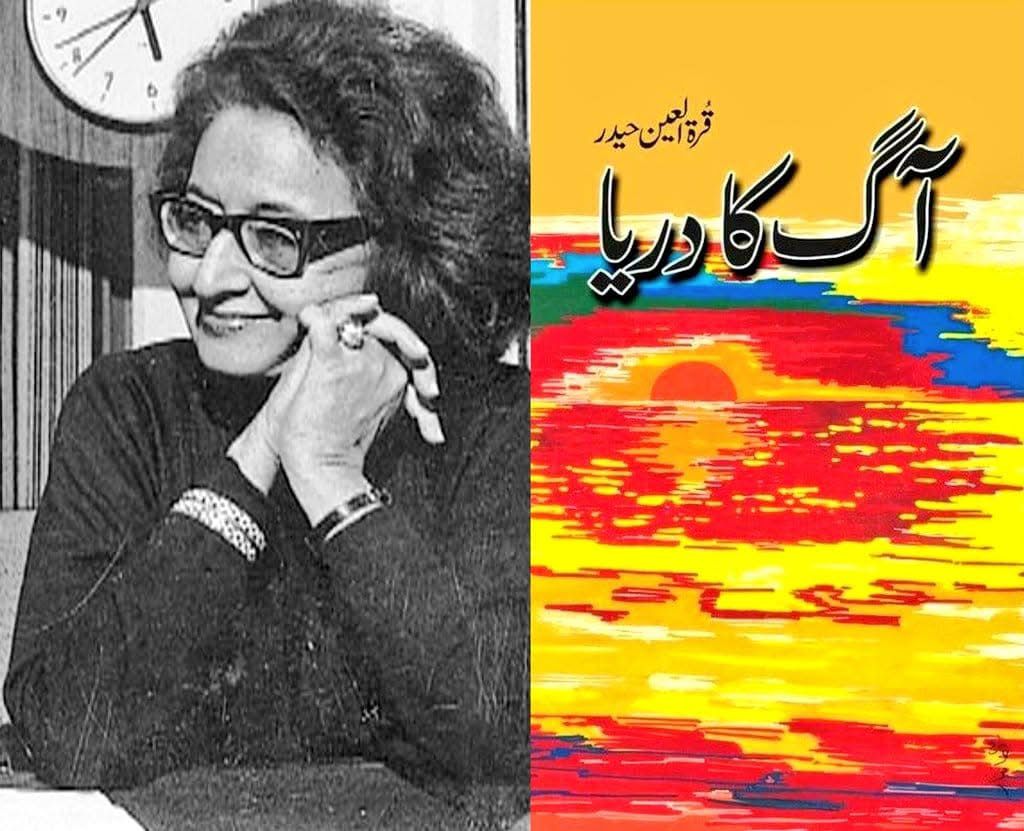

My tribute to the great Urdu writer and novelist Qurratulain Hyder on her 18th death anniversary

The relevance and significance of her magnum opus “Aag Ka Darya” in understanding the composite Indian civilisation

Qurratulain Hyder’s River of Fire: Remembering the Grande Dame of Urdu Literature

A Writer Beyond Borders

Eighteen years ago, on August 21, 2007, Urdu literature lost one of its most luminous stars—Qurratulain Hyder. Widely known as “the Grande Dame of Urdu fiction,” Hyder transformed the Urdu novel into a serious artistic and intellectual form. Her magnum opus, Aag Ka Darya (River of Fire), published in 1959, remains not just her masterpiece but also one of the greatest novels ever written in the Indian subcontinent.

Born in 1927 in Aligarh to a literary family—her father Sajjad Hyder Yildirim and mother Nazar Zahra were both writers—Hyder grew up immersed in books and debates. Educated in Lucknow, she witnessed Partition firsthand, moving briefly to Pakistan before returning permanently to India in 1961. She went on to receive the Sahitya Akademi Award, the Jnanpith Award, and the Padma Bhushan, but her most lasting legacy remains her reimagining of India’s past through fiction.

A River of Time and Memory

Aag Ka Darya is no ordinary novel. It is a vast historical canvas that stretches across 2,000 years of Indian civilisation. Hyder follows four recurring characters—Gautam, Champa, Kamal, and Cyril—who reappear across different epochs in new roles.

The story begins in ancient India with Nilambar Gautam, a student at the forest universities where Buddhist thought was spreading. As time shifts to the Mughal period, Gautam reappears as Kamaluddin, a scholar from Baghdad, while Champa and Hari take new forms. Later, the British colonial period introduces Cyril Ashley, an Englishman whose presence reflects the European impact on India. Finally, the characters resurface in the 20th century, confronting the turmoil of Partition.

Through these cycles, Hyder shows how identities change, cultures mingle, and history repeats. The novel suggests that Indian civilisation is less a straight line and more a river—sometimes turbulent, sometimes calm, but always flowing.

Composite Civilisation at the Core

What makes River of Fire extraordinary is its vision of India’s composite culture. For Hyder, the subcontinent was not a mosaic of separate communities but a shared civilisation shaped by centuries of dialogue between Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim, and later Western traditions.

In lyrical prose that blends Sanskrit verses, Persian couplets, and Urdu poetry, Hyder portrays how conquests and encounters created a rich cultural fabric. She acknowledges conflict but insists that the true genius of India lies in its ability to absorb, adapt, and coexist.

It is this vision that made Aag Ka Darya so controversial in Pakistan, where critics saw it as “too Indian.” In India, however, it was celebrated as a masterpiece that reclaimed a plural past against the divisive logic of Partition.

Comparisons and Global Standing

Hyder’s epic has often been compared to Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and Milan Kundera’s novels about memory and history. Yet, River of Fire is distinct—it is less magical realism and more philosophical history. If Márquez gave Latin America its mythic novel, Hyder gave India its civilisational epic.

Her command of multiple traditions—classical, Persian, Urdu, and English—allowed her to write with rare erudition. At times dense, the novel demands an “inquisitive reader,” but it rewards those willing to dive into its layered depths.

The Partition Wound

The final chapters of Aag Ka Darya bring the story into the 20th century and the “river of fire” that was Partition. Here, Hyder captures the pain of a civilisation torn apart by politics. Her recurring characters now stand at the crossroads of history, questioning whether centuries of shared culture can survive the sudden rupture of borders.

Hyder herself lived this dilemma. Though she spent some years in Pakistan, she chose to return to India, aligning with the very vision her novel articulated: that despite Partition, the river of India’s composite civilisation must continue to flow.

Why Hyder Matters Today

Eighteen years after her passing, Qurratulain Hyder’s message feels more urgent than ever. At a time when histories are often rewritten to emphasise division, Aag Ka Darya reminds us of a deeper truth—that the story of India is one of mingling, not separation.

The novel does not idealise the past; it acknowledges wars, hierarchies, and ruptures. But it also insists that culture is created not through isolation but through encounter. To read Hyder today is to confront the possibility that the “river of fire” is still burning—but also to remember that rivers endure, however scarred.

The Fire That Still Burns

Qurratulain Hyder gave Urdu literature its most ambitious novel and South Asia one of its finest epics. Aag Ka Darya is not merely a story but a philosophy of history—a reminder that civilisations are not pure streams but confluences of many rivers.

On her death anniversary, revisiting River of Fire is more than an act of literary homage; it is a return to an idea of India rooted in pluralism, dialogue, and shared memory. Hyder’s river still flows, carrying within it both the fire of history and the promise of continuity.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai