Fifty years ago, India witnessed a seismic jolt to its democratic foundations when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared a national Emergency on June 25, 1975. The move, widely regarded as a dark chapter in India’s constitutional history, suspended civil liberties, muzzled the press, and stifled dissent for 19 months. Today, as the nation reflects on that turbulent period, the ruling Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) has designated June 25 as Samvidhan Hatya Diwas (Constitution Murder Day), a symbolic reminder of the assault on democracy. Yet, a parallel narrative emerges—one that questions whether the spirit of that Emergency lingers in subtler, more insidious forms under the current regime led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

This article explores the Emergency of 1975-77 and contrasts it with contemporary challenges to India’s democratic fabric, drawing parallels and highlighting differences with fresh examples and factual depth.

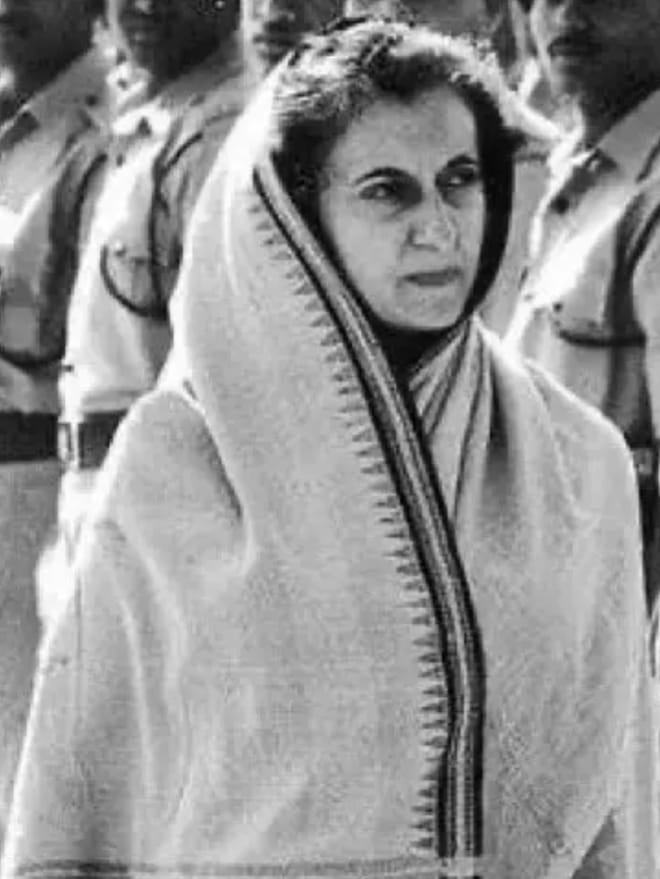

The Emergency of 1975: A Constitutional Coup

On the night of June 25, 1975, Indira Gandhi, citing “internal disturbances,” invoked Article 352 of the Constitution, plunging India into a state of Emergency. Civil liberties were suspended, political opponents were jailed, and the press was subjected to strict censorship. The Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) became a tool to detain thousands without trial, including prominent leaders like Jayaprakash Narayan and Morarji Desai. According to reports, over 100,000 people were arrested during the 19-month period. The judiciary, meant to be a bulwark of democracy, was rendered toothless, with the Supreme Court’s infamous ruling in ADM Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla (1976) upholding the suspension of habeas corpus, effectively endorsing the executive’s unchecked power.

The media faced unprecedented repression. Newspapers like The Indian Express and The Statesman published blank editorials in protest, while others were coerced into towing the government line. The forced sterilization campaign, led by Sanjay Gandhi, became a symbol of authoritarian overreach, with millions subjected to coercive procedures—official records estimate 6.2 million sterilizations in 1976 alone, often targeting marginalized communities. The Emergency ended in March 1977, when Indira Gandhi’s Congress party was decisively defeated in the general elections, paving the way for the Janata Party to restore democratic norms.

The 44th Constitutional Amendment in 1978, enacted under the Janata government, ensured that a national Emergency could no longer be declared on the vague grounds of “internal disturbance.” This safeguard was a direct response to the excesses of 1975-77, aiming to protect India’s democratic framework from similar assaults. Yet, the scars of the Emergency remain a potent reminder of how fragile democracy can be when power is concentrated.

The Gujarat Riots of 2002: A Different Kind of Crisis

Fast forward to 2002, under Narendra Modi’s tenure as Gujarat’s Chief Minister, another grim chapter unfolded. The Godhra train burning incident, where 59 Hindu pilgrims died, sparked widespread communal violence. Over 1,000 people, predominantly Muslims, were killed, with unofficial estimates suggesting a higher toll. The riots, marked by brutal mob violence, arson, and targeted killings, left a deep wound on India’s secular fabric. Human Rights Watch and other organizations documented allegations of state complicity, pointing to delayed police action and political patronage of rioters. The Supreme Court later criticized the Gujarat government’s handling of the situation, transferring key cases out of the state to ensure impartiality.

The 2002 riots, while not a formal Emergency, raised questions about governance and accountability. Modi’s administration was accused of failing to protect minorities, with critics arguing that the violence was tacitly enabled to consolidate Hindu majoritarian support. The aftermath saw Modi’s political rise, culminating in his ascent to the Prime Minister’s office in 2014. For many, the Gujarat riots symbolize a different kind of emergency—one not declared by constitutional fiat but executed through selective inaction and polarizing rhetoric.

The Undeclared Emergency

Prime Minister Modi has repeatedly vowed that the Emergency of 1975 will never return. Yet, critics argue that his tenure has normalized a subtler form of authoritarianism, bleeding democracy through “a thousand cuts.” Unlike Indira Gandhi’s overt suspension of constitutional rights, the current regime is accused of undermining democratic institutions through incremental, often covert, means. Below are key areas where this comparison holds:

Media: From Censorship to Collaboration

During the Emergency, the government imposed formal censorship, requiring pre-publication approval of news content. Today, while no such decree exists, India’s media landscape is under strain. The 2024 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders ranked India 161 out of 180 countries, citing “unofficial censorship” and pressure on journalists. Prominent media houses are often accused of aligning with the government, amplifying its narrative while side lining critical voices. For instance, the coverage of the 2019 abrogation of Article 370, which revoked Jammu and Kashmir’s special status, saw mainstream outlets largely echoing the government’s perspective, with little space for dissent. Independent journalists face harassment, with cases like Siddique Kappan’s arrest in 2020 for reporting on a sensitive issue in Uttar Pradesh highlighting the risks of critical journalism.

Institutional Weaponization

The Emergency saw the misuse of laws like MISA to silence opponents. Today, laws like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and sedition provisions are often criticized for targeting activists, students, and journalists. The 2020 Delhi riots, which claimed 53 lives, predominantly Muslims, led to the arrest of several activists under UAPA, including Umar Khalid, who remains in jail without trial. Such cases fuel allegations that investigative agencies like the Enforcement Directorate (ED) and Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) are being weaponized against political adversaries, much like during the Emergency.

Judicial Compromise

The judiciary’s role during the Emergency was marred by its acquiescence to executive overreach. Today, critics point to instances where the judiciary appears deferential to the government. The “sealed cover” practice, where evidence is submitted to courts without public disclosure, has been used in high-profile cases, such as the Rafale deal controversy, raising concerns about transparency. The Supreme Court’s handling of cases like the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) protests or the abrogation of Article 370 has also drawn criticism for delays or perceived alignment with the executive.

Vigilante Violence and Majoritarianism

The rise of vigilante groups acting in the name of “protecting Hindu culture” has been a hallmark of the past decade. Cow vigilantism, for instance, has led to numerous lynching’s, with victims predominantly from minority communities. According to a 2023 report by India Spend, 63% of hate crimes between 2010 and 2022 targeted Muslims. Incidents like the 2015 lynching of Mohammad Akhlaq in Dadri or the 2017 killing of Pehlu Khan in Rajasthan exemplify this trend. Critics argue that such acts enjoy implicit state protection in BJP-ruled states, where perpetrators often face delayed or lenient prosecution.

Small is Beautiful: Modi’s Masterclass in Subtle Control

Indira Gandhi’s Emergency was a blunt instrument, alienating large sections of society. In contrast, Modi’s approach is surgical, leveraging majoritarian sentiment, media compliance, and legal mechanisms to consolidate power without formally suspending the Constitution. The abrogation of Article 370, the passage of the CAA, and the construction of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya are portrayed as democratic triumphs by supporters, yet they have deepened communal fault lines. The use of technology, such as social media campaigns and WhatsApp groups, has amplified divisive narratives, creating an ecosystem where dissent is marginalized without the need for formal censorship.

A Democracy at Crossroads

The Emergency of 1975 was a fleeting, albeit brutal, assault on India’s democracy, reversed by the electorate’s verdict in 1977. Today’s challenges, while less overt, are no less threatening. The normalization of majoritarianism, institutional erosion, and self-censorship signal a democracy under strain. As India commemorates 50 years since the Emergency, the nation must reflect not only on past excesses but also on present vulnerabilities. The question is not whether an Emergency can return in its 1975 form—it cannot, thanks to constitutional safeguards—but whether democracy can withstand the subtler, more pervasive threats of today. Only a vigilant citizenry, an independent media, and a robust judiciary can ensure that India’s democratic project endures, unscarred by the ghosts of emergencies past and present.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai