75 Years of the Election Commission of India: It’s Role, Responsibilities and Controversies The Election Commission of India at 75: A Beacon of Democracy Amidst Challenges and Controversies

As the Election Commission of India (ECI) marks its 75th year since its establishment on January 25, 1950, it stands as a cornerstone of Indian democracy, tasked with the monumental responsibility of conducting free and fair elections in the world’s largest democratic exercise. Entrusted with overseeing elections to the Parliament, state legislatures, and the offices of the President and Vice-President, the ECI has been instrumental in shaping India’s democratic ethos. However, its journey has been punctuated by significant achievements, transformative reforms, and persistent controversies, including recent allegations of voter suppression and concerns over transparency in the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) process.

This article explores the ECI’s pivotal role, its evolving responsibilities, and the controversies that have tested its credibility over the decades.

The ECI’s Role: The Bedrock of Indian Democracy

The ECI, established under Article 324 of the Indian Constitution, is a constitutional body designed to ensure that India’s democratic processes remain robust and impartial. Headquartered at Nirvachan Sadan in New Delhi, the commission, led by a Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) and two Election Commissioners, operates with a staff of approximately 300 and a vast network of state and district-level officers. Its responsibilities are multifaceted, encompassing voter registration, electoral roll preparation, political party regulation, enforcement of the Model Code of Conduct (MCC), expenditure monitoring, and dispute resolution. The ECI’s initiatives, such as the Systematic Voters’ Education and Electoral Participation (SVEEP) programme have significantly boosted voter awareness, particularly among marginalized communities.

The commission’s technological innovations, such as the introduction of Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) in 1982 and the Voter-Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) in 2013, have streamlined the voting process and enhanced transparency. The inclusion of the None of the Above (NOTA) option in 2013 further empowered voters to express dissent, reinforcing the ECI’s commitment to democratic principles.

Over the years, the ECI has conducted elections on an unparalleled scale, managing over 900 million voters in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections alone, a testament to its logistical prowess.

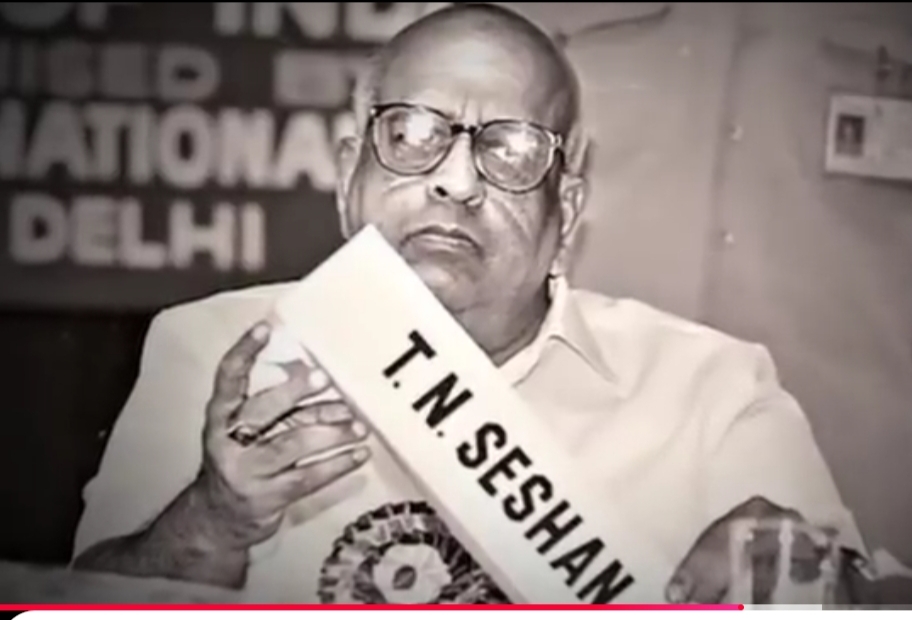

T.N. Seshan’s Legacy: A Turning Point for the ECI

The ECI’s stature as a formidable institution owes much to the transformative tenure of T.N. Seshan, who served as CEC from 1990 to 1996. Prior to Seshan, the ECI was often criticized for its perceived weakness and inability to curb rampant electoral malpractices like booth capturing, voter bribery, and misuse of government machinery. Seshan’s fearless approach revolutionized the commission’s role. He enforced the MCC with unprecedented rigor, canceling elections in constituencies marred by irregularities and holding powerful politicians accountable. His introduction of Electors’ Photo Identity Cards (EPICs) in 1993 was a landmark step in curbing voter impersonation.

Seshan’s assertive leadership not only restored public faith in the ECI but also set a precedent for its independence. His tenure is often credited with transforming the commission from a passive overseer to a proactive guardian of electoral integrity. However, his confrontational style also drew criticism, with some accusing him of overstepping his mandate. Nonetheless, Seshan’s legacy endures as a benchmark for the ECI’s authority and impartiality.

Controversies Through the Years

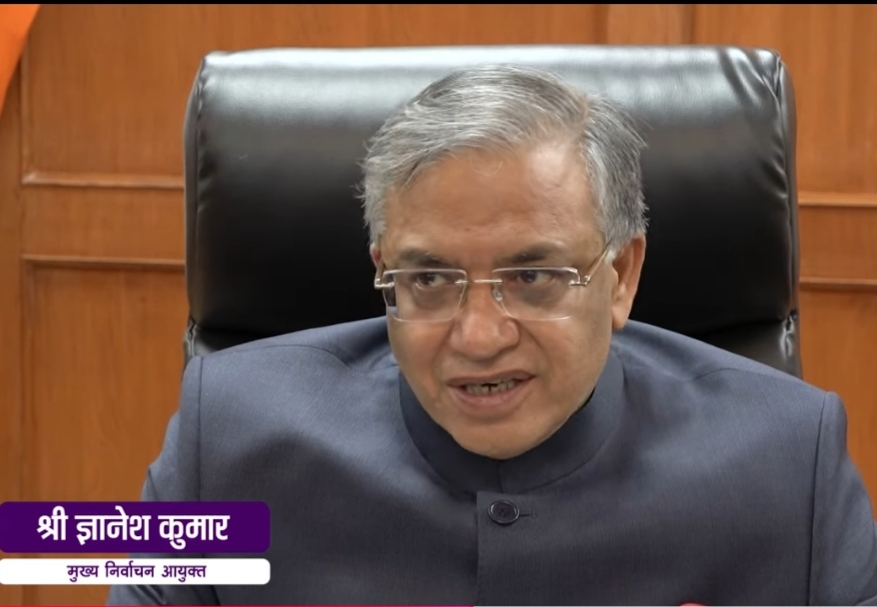

Despite its achievements, the ECI has faced persistent scrutiny over its autonomy, enforcement mechanisms, and technological choices. One of the most contentious issues has been the appointment process for Election Commissioners. Historically, the President appointed commissioners based on the Prime Minister’s recommendations, raising concerns about executive influence. In March 2023, the Supreme Court mandated a selection committee comprising the Prime Minister, the Leader of the Opposition, and the Chief Justice of India to ensure transparency. However, the 2023 Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners Act replaced the Chief Justice with a Union Minister nominated by the Prime Minister, reigniting debates about political interference.

The ECI’s enforcement of the MCC has also been a flashpoint. Critics argue that the commission has been inconsistent in addressing violations, particularly by influential political figures. During the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, over 200 complaints of booth capturing, voter intimidation, and EVM malfunctions were reported in Uttar Pradesh alone, yet the ECI’s response was perceived as inadequate by some opposition parties. The commission’s failure to act swiftly against “Star Campaigners” using divisive rhetoric has further fueled accusations of selective enforcement.

The use of EVMs and VVPATs has been another contentious issue. While EVMs have reduced electoral fraud, allegations of tampering have persisted, particularly after high-stakes elections. The limited verification of VVPAT slips—currently restricted to five polling stations per assembly constituency—has drawn criticism for being insufficient to address widespread concerns. In 2017, the ECI organized an open hackathon to demonstrate the security of EVMs, but the event failed to quell skepticism, as no participants attempted to hack the machines.

The Special Intensive Revision (SIR) Controversy

The ECI’s recent Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar ahead of the 2025 Assembly elections has sparked significant controversy. The process, which led to the deletion of approximately 65 lakh voter names, has been criticized for its lack of transparency and public consultation. Opposition leaders, including Congress leader Rahul Gandhi, have labelled these deletions as “vote theft,” alleging that they disproportionately target marginalized and migrant communities, potentially disenfranchising vulnerable voters. Gandhi’s accusations, amplified on social media platforms have intensified scrutiny of the ECI’s processes, with critics arguing that such large-scale deletions without clear justification undermine democratic inclusivity.

The SIR controversy highlights broader issues with voter list accuracy. Duplicate entries, outdated information, and wrongful exclusions have long plagued electoral rolls.

In Bihar, the scale of deletions has raised fears of systematic disenfranchisement, particularly among communities with limited access to documentation or digital platforms. The ECI has defended the SIR as a necessary exercise to maintain electoral integrity, but its failure to provide detailed public explanations has eroded trust.

Rahul Gandhi’s Allegations and Political Tensions

Rahul Gandhi’s “vote theft” allegations, made in August 2025, have added a new dimension to the ECI’s challenges. Gandhi claimed that the SIR process was a deliberate attempt to suppress opposition voters, citing the lack of transparency in how names were removed. These accusations resonate with broader concerns about the ECI’s impartiality, particularly in light of its perceived leniency toward ruling party violations during past elections. Social media posts have echoed Gandhi’s sentiments, with users highlighting the need for greater accountability in voter roll revisions.

The ECI has responded by asserting that the SIR was conducted per established protocols, with opportunities for voters to rectify errors. However, the commission’s limited engagement with affected communities and its reluctance to disclose the criteria for deletions have fueled suspicions. This controversy underscores the delicate balance the ECI must strike between maintaining electoral integrity and ensuring inclusivity, particularly in a polarized political climate.

Ongoing Challenges and the Path to Reform

The ECI faces several ongoing challenges that threaten its credibility. The criminalization of politics remains a significant concern, with 46% of elected MPs in 2024 facing criminal cases, according to the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR). The ECI’s support for a lifetime ban on convicted felons from contesting elections has yet to translate into policy, highlighting the need for legislative backing. Unregulated election expenditure, estimated at ₹1,00,000 crore in 2024, continues to create an uneven playing field, with wealthier parties dominating campaigns.

Low representation of women and marginalized groups is another pressing issue. Despite the Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam, 2023, promising 33% reservation for women in legislatures, its implementation is delayed until 2029. Migrant voters face logistical barriers, and the ECI’s proposal for Remote Voting Machines (RVMs) has met skepticism over feasibility and security. Additionally, the lack of inner-party democracy perpetuates dynastic politics, with 30% of 2019 Lok Sabha MPs hailing from political families.

To address these challenges, several reforms have been proposed. *Simultaneous elections, as advocated by the Kovind Committee, could reduce costs and governance disruptions.

However, the idea of One Nation One Election has its own inherent limitations and it’s being hotly debated in the parliament and other forums.

*Strengthening the MCC’s enforcement through measures like revoking “Star Campaigner” status for violators would enhance fairness. *Increasing the ECI’s financial autonomy by charging its budget to the Consolidated Fund of India could reduce executive influence.

*Fast-track courts for political criminal cases and mandatory inner-party elections could curb criminalization and dynasticism. *Finally, expanding VVPAT verification and introducing guidelines for digital campaigning would bolster transparency and trust.

A Future-Ready Electoral System

As the ECI celebrates 75 years, it remains a vital pillar of Indian democracy, navigating the complexities of conducting elections on an unprecedented scale. Its achievements, from technological innovations to voter awareness campaigns, have strengthened India’s democratic fabric. However, persistent controversies, including the SIR debacle and allegations of vote theft, underscore the need for greater transparency, accountability, and inclusivity. By embracing reforms that prioritize empowerment, equity, efficiency, and ethics, the ECI can address its challenges and reinforce its role as a global beacon of democracy. As India evolves, the commission must adapt to safeguard every voter’s voice, ensuring that the spirit of democracy thrives for generations to come.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai

~Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai