In Indian political memory, few events evoke such stark fear and regret as the Emergency imposed by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi between June 1975 and March 1977. This 21 Months period is rightly considered a dark chapter in India’s democratic history—a time when civil liberties were curtailed, opposition leaders jailed, press freedoms suspended, and authoritarianism briefly took center stage. However, nearly five decades later, a critical reappraisal of the Emergency and its aftermath offers not just historical insight but also urgent parallels with contemporary political realities.

The popular narrative is well known: faced with a political and legal crisis following her conviction for electoral malpractices, Indira Gandhi clamped down on dissent, invoking Article 352 of the Constitution and declaring a state of internal emergency. Thousands of opposition leaders were imprisoned. Fundamental rights were suspended. Media was gagged. The judiciary, under pressure, faltered. It was, by all accounts, an assault on the very foundations of constitutional democracy.

Yet, what is equally significant—and perhaps under-discussed—is what happened after the Emergency ended. Despite wielding absolute power and commanding the loyalty of the state machinery, Indira Gandhi took the political gamble of announcing fresh elections in March 1977. Against the advice of many close to her, and with full knowledge of the risks involved, she called upon the people to decide her fate. The Congress party was routed. The Janata Party, a coalition of anti-Emergency forces, came to power. The transition was peaceful and democratic.

This willingness to submit to public verdict, even after an authoritarian episode, is a critical marker of Indian democracy’s resilience in the 20th century. What’s even more telling is that the elections were largely free and fair—despite Congress’s vast resources and influence. No EVM tampering. No large-scale disenfranchisement. No bureaucratic sabotage. The people spoke, and the regime fell.

But what followed is even more curious. After two years of Janata Party rule, marked by internal contradictions and policy paralysis, the Indian electorate chose to bring Indira Gandhi back to power in 1980. This return wasn’t due to nostalgia or forgetfulness. It reflected a complex understanding among the electorate—an acknowledgment of her leadership skills, willingness to accept electoral defeat, and perhaps the belief that the Emergency was a deviation, not a norm.

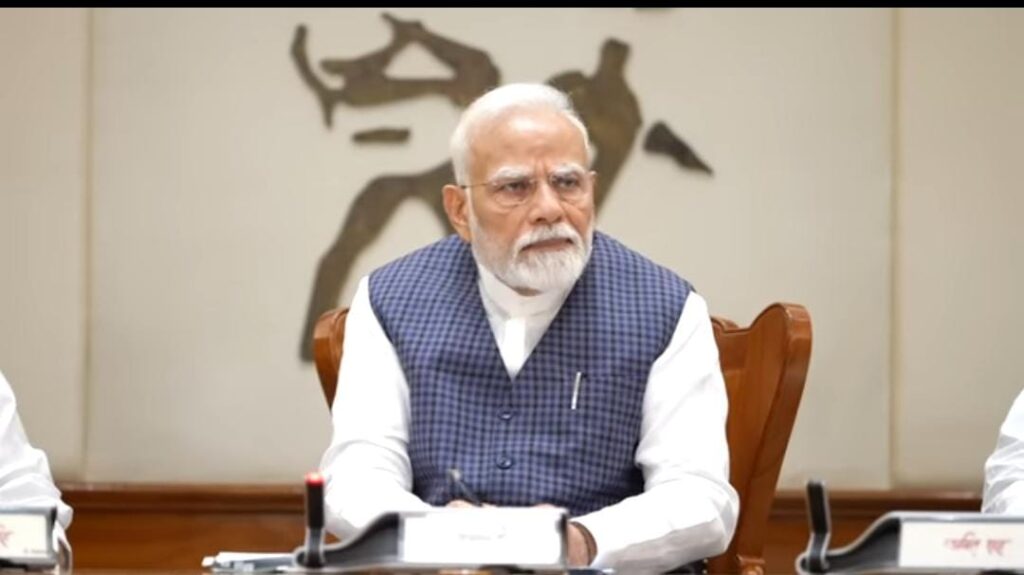

This brings us to the present—more than a decade into the rule of a new political dispensation that came to power in 2014 on the promise of strong leadership, national security, and developmental governance. Since then, India has witnessed the rise of a dominant party-state apparatus that many argue is far more systematic and enduring in undermining democratic institutions than the Emergency ever was.

The comparison is not to justify or diminish the Emergency. It is rather to highlight a crucial difference: the Emergency was overt, declared, and time-bound. It was enacted with constitutional sanction (however misused), and its beginning and end were both clearly marked. What India is witnessing now, critics argue, is a silent, rolling emergency—undeclared but omnipresent. A political climate where dissent is criminalized, media houses are silenced through economic coercion or raids, academic spaces are intimidated, and opposition leaders routinely face investigative agencies before elections.

The erosion is subtle but systematic. The Election Commission, once revered as fiercely independent, has come under suspicion over the timing of decisions, transfers of officials, and delays in announcing election schedules. The judiciary, too, appears hesitant to challenge executive overreach, especially on issues of civil liberties and electoral transparency. Institutions meant to act as checks and balances increasingly behave like extensions of the ruling regime.

One may argue that these developments, while disturbing, are still part of a democratic framework. Elections are held regularly. Parliaments function. Newspapers still publish. Social media allows some space for criticism. But the question is not about form—it’s about substance. Is Indian democracy merely ticking procedural boxes while its spirit is being hollowed out?

Consider the case of press freedom. During the Emergency, censorship was official. Editors were ordered to submit stories for government clearance. In response, many newspapers left their editorial columns blank—a powerful act of resistance. Today, censorship is unofficial but no less effective. Media houses that challenge the government risk income-tax raids, loss of advertisers, or legal harassment. Instead of banning coverage, the system ensures that critical voices are outpriced, outnumbered, or algorithmically drowned in noise.

Similarly, during the Emergency, the arrest of opposition leaders was widespread but clearly political and temporary. Today, opposition leaders are booked under serious charges like money laundering or sedition, often without convictions, creating a chilling effect. They are denied bail while investigations drag on indefinitely. The process, as they say, becomes the punishment.

The abuse of technology in elections also marks a dangerous departure. While Indira Gandhi had the state machinery at her disposal, she did not manipulate the 1977 elections, even when defeat seemed certain. In contrast, today’s India is grappling with allegations of targeted voter deletions, biased election scheduling, the misuse of social media to spread disinformation, and opaque electoral bonds that favor the ruling party. Faith in the electoral process—the very foundation of democracy—is weakening.

Moreover, civil society voices and grassroots movements, once celebrated as the conscience-keepers of the nation, are now branded as “anti-national” or “urban Naxals.” Foreign-funded NGOs have faced arbitrary crackdowns. Activists are jailed under draconian laws like UAPA, often without trial. Student leaders are vilified on primetime television and denied space in mainstream political discourse.

This creeping authoritarianism is masked by the rhetoric of nationalism and development. The narrative is no longer about constitutional values, pluralism, or debate. It is about loyalty to one leader, one party, one idea of the nation. Any deviation is painted as betrayal.

In such a context, the Emergency—despite its grave excesses—can paradoxically appear more honest. It was a declared deviation, and it ended with an election. What India faces today is far more insidious: a normalisation of undemocratic practices, a redefinition of patriotism as submission, and the steady erosion of all democratic safeguards through legal, electoral, and institutional capture.

History will undoubtedly continue to condemn the Emergency. But it may also note that, in the end, Indira Gandhi did not cling to power at the cost of democracy. She called for elections. She accepted defeat. And when she returned, it was through the ballot box, not brute force.

The same cannot be confidently said about today’s ruling establishment. As India moves toward the next general elections, the core challenge is no longer just about who wins. It is about whether the rules of the game remain fair, whether institutions retain independence, and whether citizens retain the right to question, resist, and organize without fear.

The Emergency taught India the price of authoritarianism. The present situation in India undoubtedly teaches us how it has already returned—openly without through multidimensional diversion tact’s and centralized Power politics without any human face.

(Writer is Senior Journalist and Political Commentator)