NEW DELHI,2 Feb 2026 : Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s union budget presented on Sunday runs a manufacturing playbook that Keynes wrote in 1933.

Liberal economists hated that ‘Self-sufficiency’ essay. India just budgeted ₹12 lakh crore on it. They’re just not calling it that.

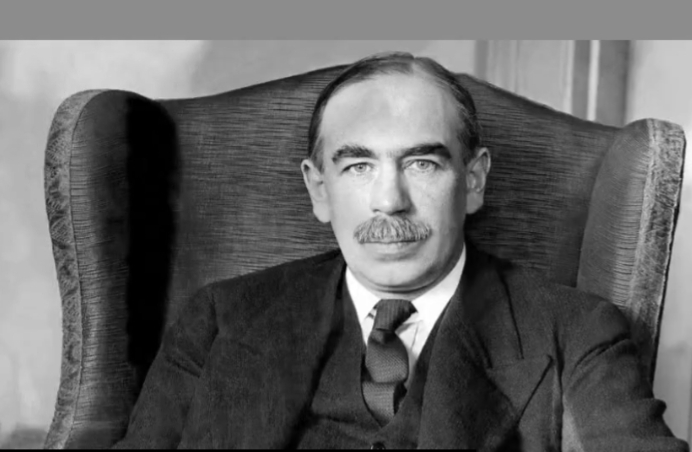

Economist John Mynard Keynes had developed a macroeconomic theory in 1930s arguing that active government intervention (fiscal and monetary policy) is necessary to manage economic cycles, boost low aggregate demand, and reduce unemployment during recessions. It advocates for increased government spending, lower taxes, and lower interest rates to stabilize volatile markets.

The essay by Keynes was called National Self-Sufficiency. The argument was simple: when global trade becomes unreliable, countries should bring production home—even if it costs more. Keynes wasn’t becoming a protectionist. He was being pragmatic. If supply chains can be weaponized, the math changes. Resilience becomes worth paying for.

Budget 2026-27 runs that exact playbook. The Finance Minister explicitly warned that “trade and multilateralism are imperilled” and supply chains are “routinely politicised.” The operational response is Keynesian in the 1933 sense: selective self-reliance as insurance against a hostile world. The word “self-sufficiency” appears nowhere. The policy is everywhere.

Here’s what that policy looks like in practice: ₹10,000 crore for biopharma over five years, three new pharmaceutical research institutes, 1,000 clinical trial sites. Electronics component manufacturing gets bumped from ₹22,919 crore to ₹40,000 crore after investment commitments reportedly doubled. A ₹10,000 crore SME Growth Fund. Seven “strategic and frontier” sectors get dedicated ecosystem funding.

This is industrial policy with a specific bet embedded in it. The bet is that global instability isn’t a phase—it’s the new normal. If that’s true, every rupee spent building domestic capacity pays off in avoided disruption. But if global trade stabilizes, if supply chains become reliable again, India has just paid an enormous premium for insurance it didn’t need.

The budget’s own language reveals the tension. It insists India must “increase exports and attract stable, long-term investment” while simultaneously building buffers against a world that can’t be trusted. Don’t confuse it for a contradiction. It’s a hedge. But hedges have costs, and those costs compound.

Consider the logic chain. Capital expenditure rises to ₹12.2 lakh crore. Fiscal deficit stays at 4.3 per cent of GDP. Debt sits at 55.6 per cent. In a tight-fiscal-space world, every rupee directed toward self-sufficiency is a rupee not spent somewhere else. The budget frames this as “risk design” rather than subsidy. But risk design still has a price tag. Someone pays.

Keynes understood this trade-off. His essay explicitly acknowledged that self-sufficiency is “expensive insurance.” The value depends entirely on how dangerous the world actually is. If the global system is genuinely fragmenting—tariffs rising, supply chains politicized, multilateral institutions hollowing out—then India’s bet is shrewd. The premium buys real protection.

But here’s the uncomfortable question the budget doesn’t answer: what’s the exit strategy? Industrial policy works when governments can stop backing bets that aren’t paying off. India’s track record on sunset clauses and milestone-based accountability is not encouraging. The budget promises “disciplined intervention.” Discipline is the hard part.

Picture credit social media