How language shapes political inclusion, exclusion, governance, and resistance—from India’s federalism to global conflicts.

Language as a Tool of Power and Identity

Language is far more than a tool for communication; it is a mechanism of power, a carrier of identity, and a political battleground. In legislative halls, election rallies, protests, and digital campaigns, language often determines who has voice, agency, and belonging. Across diverse democracies such as India, Belgium, and Sri Lanka, language is deployed to consolidate authority, preserve culture, and negotiate identity.

The historical and ongoing reorganization of Indian states along linguistic lines, as well as contemporary legal verdicts such as the Supreme Court’s 2025 ruling on Urdu, underline how central language remains to political discourse. As globalization and identity politics evolve, the relationship between language and power grows even more consequential.

Language in Politics: Propaganda, Polarization, and Persuasion

Political language is never accidental. Leaders across the globe craft slogans and narratives designed to influence, divide, or unify. In India, linguistic tailoring of election campaigns—using Tamil in Tamil Nadu or Kannada in Karnataka—fosters cultural proximity with voters. Yet, this can also tip into manipulation, as seen when populist figures employ divisive language to stigmatize minorities or foreign others.

Globally, rhetoric such as “illegal aliens” or exclusionary nationalist slogans often frames political discourse, using language to marginalize and polarize. In such instances, language becomes a tool of power consolidation rather than democratic participation.

Belonging Through Language—And Its Limits

India’s States Reorganisation Act of 1956 recognized language as central to governance, enabling communities to preserve culture and influence local policies. But linguistic demarcation also brought new tensions. The formation of Telangana out of Andhra Pradesh, driven by identity and autonomy, demonstrates how language can both unify and divide.

Internationally, Belgium’s division between Dutch-speaking Flemish and French-speaking Walloons necessitates intricate political balancing. Such linguistic fractures determine who governs and whose voice is heard in public life.

Language Policy: Balancing Nationalism and Regionalism

In multilingual democracies, language policy walks a tightrope. India’s Three-Language Formula—promoting Hindi, English, and regional languages—was meant to bridge unity and diversity. In practice, it has been contentious, especially in Tamil Nadu, where Hindi imposition is viewed as cultural dominance.

Elsewhere, Canada’s bilingualism, South Africa’s 11 official languages, and Quebec’s insistence on French all show how language policy reflects deeper societal power dynamics. Even when inclusion is constitutionally promised, actual practice often privileges dominant tongues, reinforcing hierarchies and exclusions.

Language and National Identity: Diversity or Uniformity?

While Hindi is promoted as a national language in India, many states view this as an attempt to impose cultural uniformity. The 2025 Supreme Court ruling on Urdu in Maharashtra challenged this trend, affirming the secular and syncretic heritage of Urdu by invoking the Ganga-Jamuna Tehzeeb. The judgment reasserted Urdu as an Indian language and not the sole preserve of a religious community.

Despite this legal victory, many state governments continue to defund Urdu-medium institutions and departments, undermining Article 350A of the Constitution which guarantees minority language education. The disconnect between legal recognition and policy action highlights ongoing struggles over linguistic rights.

Media, Social Platforms, and Linguistic Empowerment

Regional media and social platforms are reshaping linguistic politics. Local language news outlets now influence public opinion and electoral outcomes. Social media campaigns—such as those opposing the New Education Policy in Tamil Nadu—have used regional languages to mobilize dissent and amplify cultural pride.

However, digital platforms also reinforce linguistic hierarchies. English and Hindi dominate online spaces, while regional languages often remain marginalized. Algorithms and limited language support further deepen this divide, making it harder for minority voices to gain national traction.

India’s Linguistic History: Recognition and Resistance

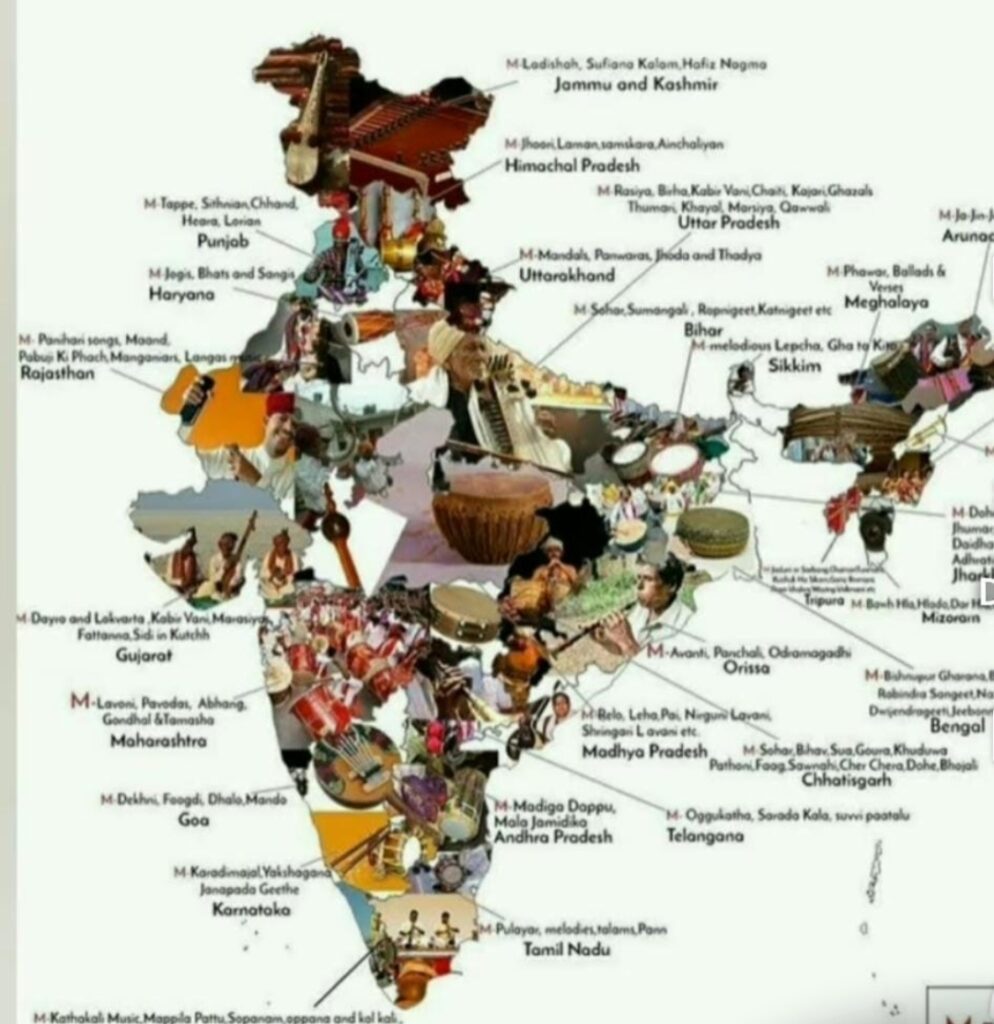

India’s linguistic diversity is immense—22 scheduled languages, over 120 major languages, and more than 1,600 dialects. The state reorganization of the 1950s was an ambitious effort to democratize this diversity. But movements for recognition—from the Bodo demand in Assam to Bhojpuri and Rajasthani campaigns—continue to challenge linguistic centralization.

Linguistic assertion is rarely about grammar; it’s about dignity, representation, and resisting dominance by hegemonic tongues in governance and media.

Dravidian Defiance: Language as Cultural Self-Assertion

The ideological divide between Hindi and Urdu has long been politicized. Historian Paul Brass notes that the Hindi-Urdu conflict symbolized deeper issues around religion and nationalism. Urdu, once patronized across communities, has increasingly been pushed to the margins post-Partition.

In contrast, South India has actively resisted Hindi hegemony. The Dravidian movement, led by Periyar, championed Tamil not just as a language but a civilization. The 1965 anti-Hindi agitations in Tamil Nadu were pivotal in asserting regional autonomy against perceived northern cultural imperialism. Today, similar resistance re-emerges in response to the NEP, particularly in Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

Campaigns in the People’s Tongue

Language has become central to political strategy. In Tamil Nadu, the DMK invokes Tamil pride to resist central dominance. In Karnataka, parties from across the spectrum appeal to Kannada identity. The BJP, traditionally aligned with Hindi nationalism, now adapts to southern linguistic sentiments—adopting regional slogans and elevating local leaders.

This multilingual political engagement reflects a deeper truth: linguistic literacy is now a prerequisite for electoral success in diverse India.

Urdu’s Cultural Reclamation : A Case Study

The Supreme Court’s 2025 ruling on Urdu reaffirmed its status as a shared cultural legacy, not a communal marker. The Court linked Urdu to India’s composite Ganga-Jamuna culture and rejected its marginalization on religious grounds.

Yet, despite this symbolic victory, implementation remains patchy. In states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar—where Urdu is an official language—it continues to face neglect in education and administration. This illustrates how language can be co-opted into religious binaries even when its heritage is syncretic.

Comparative Glimpses: Lessons from Abroad

Sri Lanka offers a cautionary tale. The Sinhala-Only Act of 1956 triggered Tamil marginalization and decades of civil conflict. In Spain, Catalonia’s linguistic nationalism fuels separatist tensions. Belgium’s federalism is mired in linguistic factionalism. These global examples underscore that denying linguistic recognition often leads to deeper political crises.

Globalization and the Vanishing Tongues

English, as a global lingua franca, enables access to opportunities—but also widens class divides and marginalizes native tongues. UNESCO warns that 40% of the world’s languages are endangered. As global platforms and educational models prioritize dominant languages, smaller tongues face extinction, taking with them cultural ecosystems.

Efforts to counter this through language revitalization, multilingual education, and inclusive policies are essential for preserving civilizational diversity.

Language as a Democratic Right

In democracies, language is not just a cultural expression—it is a democratic necessity. It grants voice, identity, and participation. The politics of language is, ultimately, the politics of dignity and recognition.

To sustain pluralism, nations must foster a linguistic landscape that is not hegemonic but inclusive—where every citizen, regardless of language, has the right to speak, be heard, and belong.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai