The Importance of Dr. Rahi Masoom Raza in the Times of Polarisation

In an era where communal divides threaten the fabric of Indian society, the life and work of Dr. Rahi Masoom Raza stand as a beacon of unity and shared heritage.

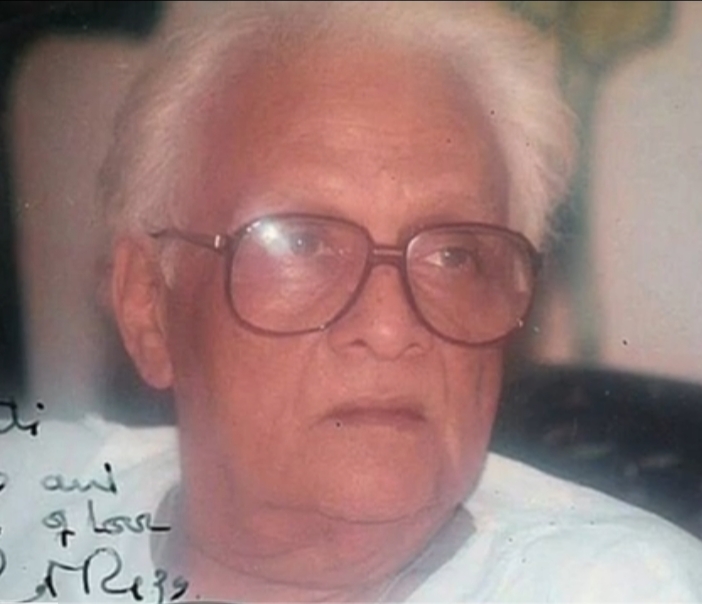

Born on September 1, 1927, in the village of Gangauli on the banks of the Ganges in Ghazipur, Uttar Pradesh—then part of the United Provinces under British rule—Raza embodied the syncretic spirit of Hindustani culture.

As we mark his 98th birth anniversary amid rising polarisation, his contributions as a poet, novelist, and screenwriter remind us of a nationalism that transcends religious boundaries.

A strong nationalist who prioritised his Indian identity over his Muslim faith, Raza opposed fundamentalism from all sides and critiqued pseudo-secularism, making him a timely figure for reflection. His writings dissected socio-political tensions, from partition’s scars to caste hierarchies, advocating for social justice and equality in a way that feels urgently relevant today.

Early Life: From Adversity to Intellectual Awakening

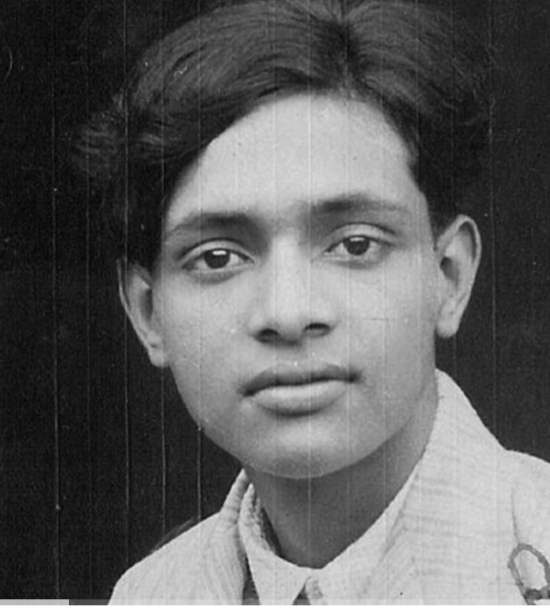

Raza’s childhood was marked by hardship that forged his resilient imagination. The younger brother of educationist Moonis Raza and scholar Mehdi Raza, he grew up in an intellectually stimulating household.

At age 11, he contracted tuberculosis, a life-threatening illness at the time, which confined him to bed and interrupted his schooling. During recovery, he devoured every book in his family’s vast collection, spanning diverse topics. To keep him company, his family employed a servant named Kallu, a masterful storyteller whose tales ignited Raza’s creative spark. Raza later credited Kallu with awakening his narrative curiosity, saying that without him, he might never have written a single story.

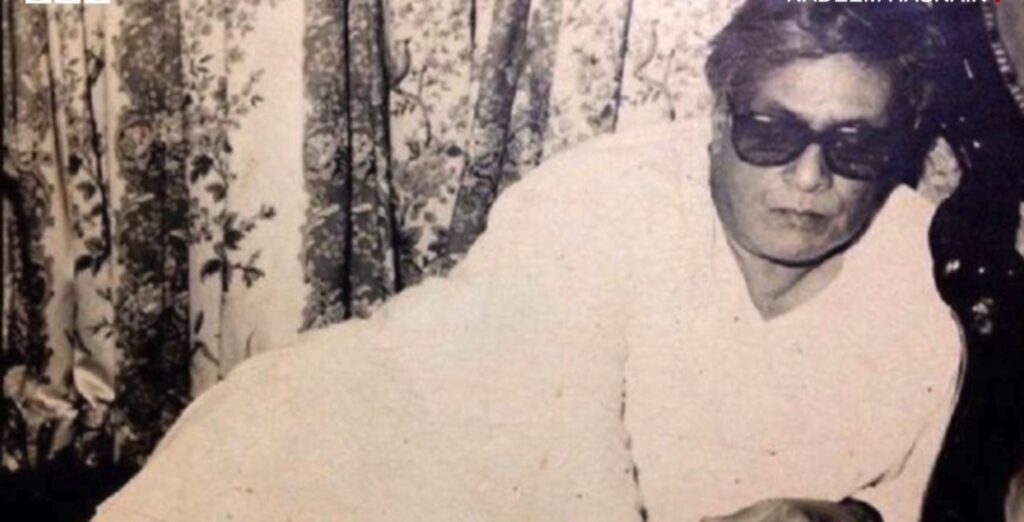

He also battled polio, another setback that temporarily halted his education. Yet, these trials built his empathy for the common man, a theme that permeated his work. After overcoming these health challenges, Raza resumed studies in Ghazipur and later enrolled at Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), where he specialised in Muslim theology and earned a doctorate in Hindustani literature. During his university days, he honed his skills by contributing to local papers and magazines. Known as the “Lord Byron of Aligarh” for his charisma, he captivated admirers—particularly young women—with his immaculate white sherwani, paan-chewing habit, and terrific sense of humour. Actor Raj Babbar later emulated these mannerisms in his role in the film Nikaah. Before venturing to Bombay (now Mumbai), Raza served as a lecturer in AMU’s Urdu department, where he developed a strong affinity for communism, influencing his progressive worldview.

Literary Journey: Chronicling India’s Complex Soul

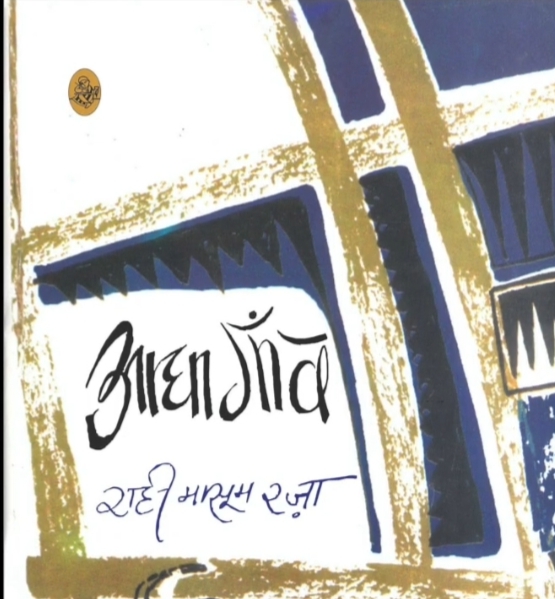

Raza’s literary output vividly captured the socio-political milieu of post-independence India, often under the pseudonym ‘Shahid Akhtar’ for the Urdu magazine Rumani Duniya from Allahabad. His novels, such as Aadha Gaon—considered on par with classics like Premchand’s Godan and Dharamvir Bharati’s Gunahon Ka Devta—portrayed the aftermath of partition and feudal life’s harsh realities in rural Uttar Pradesh. Works like Dil Ek Saada Kaghaz, Topi Shukla, Os Ki Boond, Katra Bi Arzoo, and Scene No.75 explored themes of identity, division, and human resilience. In Topi Shukla, Raza negotiated the sacred and profane, projecting counter-discourses that challenged religious orthodoxies and promoted secular humanism.

His poetry collections, including Mauj-e-Gul Maus-e-Saba and Ajnabee Shahar: Ajnabee Raste in Urdu, and Main Ek Feriwala and Sheeshe ke Makaan Wale in Hindi, reflected a deep connection to everyday struggles. Raza’s autobiography, Chotey Aadmi Ki Badee Kahaani (“Big Story of a Small Man”), further highlighted his bond with ordinary folk. Beyond these, his novels offered brutal analyses of caste discrimination, exposing the perversities and haughtiness of upper castes—a critique that resonates in today’s debates on social equity. As a robust ideologue, Raza seeded democratic values, focusing on shared histories and legacies to counter hate and discrimination. In novels like Adha Gaon, he mapped daily life experiences to unpack the politics of religion during partition, showing how communal poison disrupts communal harmony.

Foray into Cinema and Television:

Weaving Poetry into Dialogue

Raza’s transition to Bollywood in the 1970s showcased his unique ability to blend poetic flair with cinematic storytelling.

His first dialogue credit was for K.P. Atma’s Mehmaan (1971), followed by films like Parchhaiyan (1972), Raaste Kaa Patthar (1972), Bindiya Aur Bandook (1972), Patthar Aur Payal (1974), Prem Kahani (1974), Sagina (1974), Mili (1975), Bairaag (1976), Alaap (1977), Gol Maal (1979), Sawan Ko Aane Do (1979), Karz (1980), Judaai (1980), Hum Paanch (1980), Naram Garam (1981), Rocky (1981), Bemisal (1982), Disco Dancer (1982), Andhaa Kaanoon (1983), Jaag Utha Insan (1984), Saveray Wali Gaadi (1984), Sunny (1984), Jhoothi (1985), Tawaif (1985), Anokha Rishta (1986), Dahleez (1986), Aakhree Raasta (1986), Baat Ban Jaye (1986), Naache Mayuri (1986), Awam (1987), Imaandaar (1987), Naqab (1988), Goonj (1989), Jawani Zindabad (1990), Lamhe (1991), Parampara (1992), and Aaina (1993). He also penned lyrics for films such as Alaap, Goonj, Aye Mere Dil, Do Shikari, and Nirvana, collaborating with Jagjit Singh on the album Des Mein Nikla Hoga Chand.

His mastery earned him the Filmfare Best Dialogue Award three times: in 1979 for Main Tulsi Tere Aangan Ki, in 1986 for Tawaif, and posthumously in 1992 for Lamhe. Another novel, Neem Ka Ped, was adapted into a TV serial starring Pankaj Kapur, SM Zaheer, and Nimay Bali, with its theme song “Munh” written by Nida Fazli and sung by Jagjit Singh. Through these, Raza infused scripts with a progressive lens, addressing social causes without preachiness.

The Mahabharat Saga: A Stand Against Division

Raza’s crowning achievement was the screenplay and dialogues for the 1988 TV series Mahabharat, which brought the epic to millions. When B.R. Chopra approached him, Raza initially declined, citing the immense study and pressure involved, especially with his other commitments. However, news of his potential involvement sparked backlash: Hindutva groups questioned why a Muslim was chosen, while some Muslim organisations decried the offer. Chopra forwarded these letters to Raza, who, after reading them, defiantly accepted, declaring, “This time no one else will write the screenplay of Mahabharata except me. I will write because I am also the son of Ganges.”

The serial’s broadcast unleashed a flood of praise for Raza’s scholarship. Iconic elements like the opening line “Main Samay Hoon” and familial addresses such as “Matashree,” “Pitashree,” “Bhratashree,” and “Tatshree”—innovations never used in prior religious adaptations—became cultural touchstones. Raza masterfully balanced Sanskrit and Hindi, highlighting the epic’s complexities in a relatable style. Amid bundles of appreciative letters, he kept a small separate stack of abusive ones from extremist groups, noting it encouraged him: the good-hearted far outnumbered the venomous. This anecdote underscores a vital lesson—that communal poison, though loud, is outnumbered by goodwill—especially poignant in today’s fractured discourse.

Personal Life and Enduring Legacy

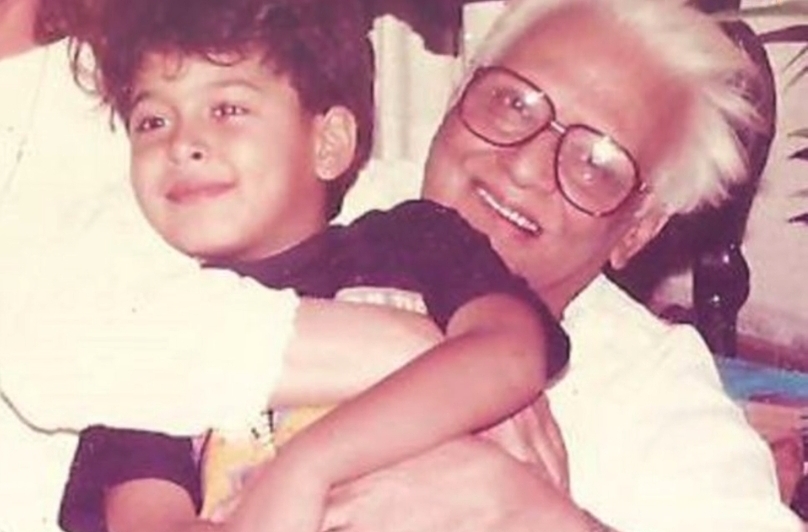

Raza’s heart found partnership in Nayyar Jahan, whom he met in Aligarh and married in 1967 despite controversy over her prior marriage, which led to opposition and his resignation from AMU. Their bond supported his creative pursuits, enriched by shared literary and social passions. They had a son, Nadeem Khan, a film director and cinematographer married to pop singer Parvati Khan.

Raza passed away on March 15, 1992, in Bombay at age 64, leaving a legacy cherished by generations. In an interview, he lamented, “People of my religion tell me he is not Muslim and people of other religions say he is Muslim but no one asked me what I am!!”

As a secular progressive, he worried about those igniting riots as much as those eroding shared values. In polarised times, Raza’s Hindustani ethos—focusing on everydayness and common legacies—offers a counter to division. His work, unafraid to bare caste horrors or religious politics, inspires a nation free of hate.

“Zakhm jab bhi koi zehn o dil pe laga…

Zindagi ki taraf ek daricha khula….

Hum bhi goya kisi saaz ke taar thhe chote khatey rahey muskurate rahey ….

Ajnabi shaher ke Ajnabi raste meri tanhai pe muskurate rahey….

Main bahot door tak yun hi chalta raha ..

Tum bahot der Tak yaad aatey rahey”.

~Dr. Rahi Masoom Raza

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai