Tongues of Power: How Language Shapes Identity, Equity and Opportunity in Maharashtra

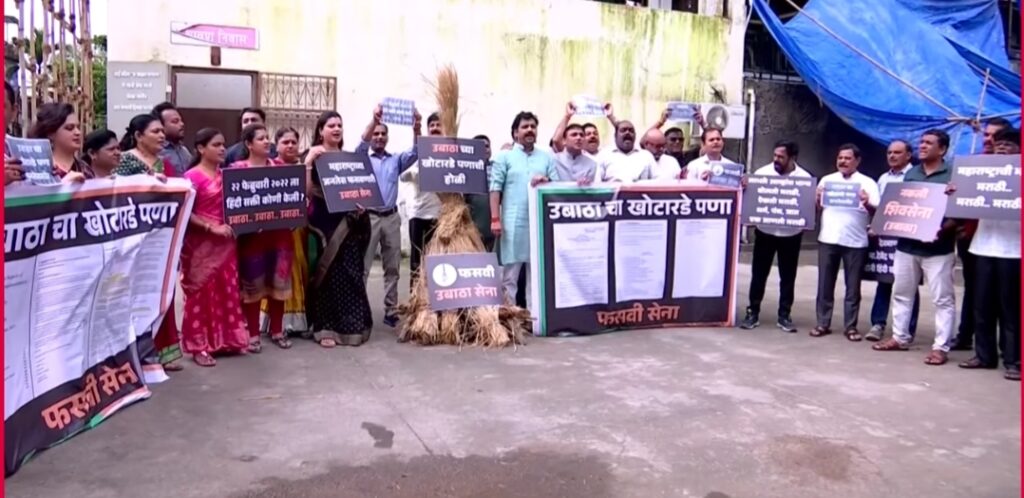

Maharashtra’s recent tussle over the three-language formula under the National Education Policy (NEP) has reopened a larger public conversation: languages are not neutral instruments of communication but political technologies that shape who we are, who gets ahead and who is left behind. The state’s oscillation — from introducing Hindi as the “general” third language for primary classes, to the issuing and then revoking of related government resolutions — illuminates a familiar tension in multilingual India: balancing regional identity, constitutional pluralism and practical questions of equity and pedagogy.

From policy to politics: what happened in Maharashtra

In June 2025 the Maharashtra government issued a Government Resolution to implement a three-language regime in Classes I–V of Marathi and English medium schools, with Hindi to be taught as the third language in most cases — albeit with a limited opt-out if enough students selected another Indian language. The move was defended by officials as an implementation of NEP 2020’s three-language objective, but it immediately provoked fierce public debate over perceived imposition and fears about Marathi’s primacy in the state. Within weeks the government backtracked, revoking earlier GRs and constituting a committee headed by educationist Narendra Jadhav to consult teachers and citizens before settling on a model.

That rapid volte-face tells us something important: language policy is never purely administrative. It is bound up with history, sentiment and the politics of majority and minority claims. In Maharashtra the memory of linguistic mobilisation — which helped create the state on the basis of Marathi identity in 1960 — is potent. Any measure perceived, rightly or wrongly, as diluting Marathi’s centrality will generate resistance. Conversely, arguments in favour of Hindi or pan-Indian multilingualism are read by some as cultural centralisation. The political heat that followed the GR made the abstract question of “what to teach” intensely personal and symbolic.

Identity: more than mother tongue sentiment

Language is a principal vehicle of identity. For many Maharashtrians, Marathi is not merely a medium of instruction but the repository of literature, public memory and social rituals. Policies that are felt to change linguistic priorities encounter a legitimacy test that administrative rationales seldom pass. That is why any top-down change in school language prescriptions must be accompanied by sustained, respectful public engagement that recognizes cultural anxieties rather than dismissing them as parochialism.

At the same time, identity is multi-layered. Urban households routinely switch registers across Marathi, Hindi, English and other languages in a single day. Many families prize multilingual competence precisely because it allows their children to inhabit multiple social worlds — the classroom, the marketplace, the national media and the global job market. The policy question is to enable that competence without turning language learning into cultural coercion.

Equity and opportunity: the English divide and the labour market

Language policy is also an equity policy. In contemporary India, proficiency in English is a crucial gateway to higher education, white-collar jobs and digital opportunity. Schools that successfully teach strong English often deliver life-changing mobility for their students; those that do not can reproduce disadvantage across generations. Thus any debate about the third language cannot ignore the existing asymmetry: mastery of regional language plus English is the economic sweet spot. For many parents the real anxiety is not Hindi versus Marathi but whether their child will be able to navigate English-medium higher education and competitive employment.

NEP 2020 explicitly emphasizes mother-tongue instruction at the foundational levels and encourages multilingualism, while also allowing states flexibility in implementation. Its intent is pedagogical — children learn better in a familiar tongue — but the implementation challenge is stark: how to combine mother-tongue instruction with the functional English skills demanded by the labour market, without overburdening young learners. The Maharashtra episode exposes the friction between these objectives.

Practical barriers: teachers, materials and classroom realities

Good policy papers mean little if classrooms lack teachers, textbooks and teacher training. Implementation problems that have dogged three-language initiatives across India resurfaced in Maharashtra: a shortage of trained teachers for additional languages, sparse teaching-learning material in several Indian languages, and administrative capacity to offer genuine choice to students in smaller schools. Even where opt-out provisions exist — such as allowing an alternative Indian language in place of Hindi when a minimum number of students opt for it — the practicalities (finding a teacher, offering assessments, maintaining quality) are major hurdles. Without addressing these supply-side constraints, any language mandate risks becoming either cosmetic or deeply injurious to learning outcomes.

Moreover, research shows that introducing multiple languages too early, or without sequential scaffolding, can burden young learners and dilute mastery of core literacy and numeracy. The Maharashtra administration briefly tried to mitigate this by limiting early years to oral skills in the third language and delaying reading and writing until later grades — a compromise that highlights the complexity of timing and pedagogy in multilingual instruction.

Politics of inclusion: minorities, migrants and linguistic pluralism

Language decisions affect minorities and migrant communities in particular. Maharashtra’s cities host linguistic and cultural minorities — Gujaratis, Urdu speakers, Telugu and Kannada migrants — whose children often attend state or municipal schools. A rigid, centrally-imposed list of languages can marginalize such groups, pushing them either to choose languages that are not useful locally or to bear the cost of private tuition. Inclusive policy must therefore preserve choice and ensure resources for minority-language instruction when needed.

Equally, states must resist simplistic binaries — Marathi vs Hindi — that polarize debate. The constitutional ethos recognises plurality: there is space for regional pride and inter-state solidarity simultaneously. NEP’s flexibility — which allows states and families to choose languages while keeping at least two Indian languages in the mix — is, in principle, designed to accommodate both impulses. The task for states is to operationalize that flexibility in ways that actually expand, rather than constrict, educational opportunity.

What good policy would look like

A few pragmatic principles should guide Maharashtra’s next steps:

1. Consultation before coercion. Language decisions must follow genuine consultations with teachers, parents and linguists — not hurried GRs — so that policy wins consent and legitimacy. The Jadhav committee’s plan for public inputs is an appropriate step; it must be thorough and transparent.

2. Focus on capacity building. Invest in teacher recruitment, multilingual textbooks, bilingual math and science materials, and training in multilingual pedagogy. Without these inputs, mandates will remain brittle.

3. Protect choice and local relevance. Allow schools and communities real choice in the third language, backed by logistical support (shared teachers, regional language resource centres) so smaller schools are not left stranded.

4. Align language and opportunity. Strengthen English teaching alongside mother-tongue instruction through immersion, digital resources and teacher upskilling so students are not forced to choose culture at the cost of career.

5. Monitor learning outcomes. Use continuous assessment to check whether multilingual instruction improves comprehension and critical thinking rather than producing superficial familiarity with multiple scripts.

Languages as bridges, not battlegrounds

Maharashtra’s recent gyrations on the three-language question should be a cautionary tale. Language is too important to be treated as a club in electoral or bureaucratic hands; yet it cannot be frozen as an untouchable symbol either. Good language policy must be pedagogical at heart and democratic in spirit: it should protect Marathi’s cultural centrality while enabling children to acquire the linguistic tools that open universities, workplaces and public life. If policy-makers treat languages as bridges to opportunity rather than badges of dominance, Maharashtra can show how a multilingual polity thrives — by making plurality a lived asset, not an occasion for fragile politicking.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai