NEW DELHI: By scrapping three decades of industrial incentives with retrospective effect, West Bengal has upended trust, undermined its own economy, and signalled hostility to capital. The fallout risks another wave of industrial flight, leaving ordinary Bengalis to suffer.

In a move that completely eludes all economic and financial understanding, the Government of West Bengal has withdrawn all incentives granted to industries in the state with retrospective effect.

The Revocation of West Bengal Incentive Schemes and Obligations in the Nature of Grants and Incentives Bill 2025, which was notified on 2 April, withdraws all incentives granted to industries since 1993, effective retrospectively from the date of implementation of each scheme. This retrospective operation is significant, as it negates benefits already accrued under schemes such as the West Bengal Incentive Schemes (1993–2021) and related support measures.

Major industrial players have now challenged the Act in the Calcutta High Court, calling it ‘unconstitutional’. The government’s decision is seen as an act of betrayal by the corporate fraternity furthering the mistrust that has been simmering between the state government and the industry.

Mega industrial houses, the Dalmia and Birla Groups have estimated a combined loss of Rs 430 crores due to the revocation while others are yet to state their figures. Industrial units that had structured investments, expansions, or financing on the legitimate expectation of receiving promised incentives now face both direct financial loss and disruption of business planning.

Going Down The Lanes Of History

West Bengal’s story of strife with industry is not a new phenomenon. The state was ruled by the communists for a long 35 years, before the baton was passed to the Trinamool Congress.

While the former, true to their ideological roots that saw corporate houses as a part of the bourgeoisie and hence an enemy force, the latter has not been kind either. The story goes that Jyoti Basu, the former Chief Minister of West Bengal and a staunch communist had once remarked that capitalists were class enemies who should not expect any sympathy.

During the dark years of the Communist Party rule, strikes and unionism were common along with violent attacks on business owners. Industry honchos realised that becoming victims of violent activities including arson is a dreadful possibility.

In due course, many gave up on business and transferred ownership. The Singhanias relocated to Delhi while the Birlas moved to Mumbai and the state that was once the second-most industrialised state of India, collapsed.

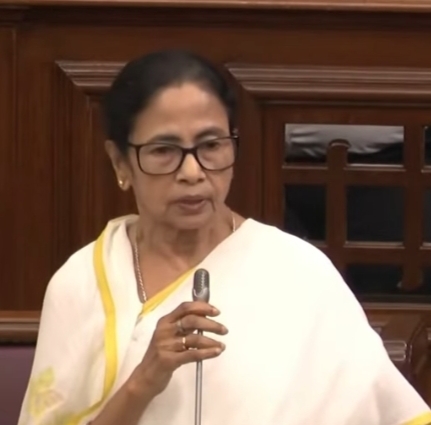

The Communists in the state were replaced by the TMC, led by Mamata Banerjee as the Chief Minister. As misfortune would have it, Banerjee’s political career was resurrected by an active agitation against the Tata Motors in Singur, one that forced the company to shift its manufacturing outside the state.

Ironically, the plant in Singur was proposed by the Communist leader, Buddhadeb Bhattacharya himself, as a means to revive industry in the state, under his new industrial policy.

The fate of the industry under the TMC rule was no different. As per the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, 6600 companies including 110 listed companies, shifted their base out of West Bengal between 2011 to 2025.

The issue has been compounded with the rising challenges of law and order coupled with illegal immigration in the state. Amidst this grim situation, thousands of workers who lost their jobs are now dependent on government aid for sustenance.

The solution to mollify the situation should have aggressive industrial promotion and incentivisation plans; however those expecting respite have instead been met with a knife to the back.

A Case For Industrial Incentivisation

Economic theory dictates the use of incentives as tools to stimulate economic growth in events of market failures. The idea becomes even more relevant when significant negative externalities have been imposed on the sector including labour woes, unfavourable social environment and law and order crisis, something that is clearly brewing in West Bengal.

Departing from the earlier theories of laissez faire, Keynes advocated for active interventions to stimulate growth by the government in times of economic downturns. Keynesian economics was critical in curing the Great Depression and increased interest developed in the same during the 2008 financial crisis.

In its present bizarre move, the West Bengal government chose to de-incentivise instead of incentivising industry even as dark clouds loom over the state economy and industry.

Several economic studies have considered the question of the efficacy of industrial incentivisation. A study from the Chinese experience, showed strong empirical evidence that subsidies have a positive effect on firms’ persistent productivity, firms with subsidies were 61.3% more productive than firms without subsidies.

Economic incentives also form an essential component of a developed nation’s industrial plans. For instance, in the US state and local governments spend at least $30 billion a year on business tax incentives. Incentives act as fiscal multipliers, one rupee spent by the government towards capital industrial incentives yields more than two rupees in benefits.

With the aim to attract investment, Government of India has started various incentivisation schemes. The Production Linked Incentives (PLI) scheme is the hallmark of this group with an impressive outlay of Rs 1.97 lakh crore.

PLI has shown impressive results with realised investments rising to about Rs 1.76 lakh crore and FDI in the large scale electronics segment increasing by 254%. While the central government has been making an aggressive push for increasing FDI and industrial investment, the West Bengal Government is leaving no stone unturned to put roadblocks in India’s growth story.

picture credit social media