Urdu Poetry’s Timeless Tributes to Lord Ganesh

In the vibrant tapestry of Indian cultural heritage, few figures embody unity and reverence as profoundly as Lord Ganesh. Revered as the god of beginnings, intellect, and obstacle removal, Ganesh has inspired devotion across religious and linguistic boundaries. Urdu poetry, with its lyrical depth and emotional resonance, has long paid homage to this elephant-headed deity, blending Islamic poetic traditions with Hindu mythology.

This fusion highlights India’s syncretic spirit, where poets from diverse backgrounds celebrate shared symbols of wisdom and prosperity.

As Ganesh Chaturthi festivities sweep the nation each year, these verses resurface, reminding us of literature’s power to bridge divides. Drawing from historical works and contemporary echoes, this article explores the rich tradition of tributes to Lord Ganesh in Urdu poetry, focusing on iconic contributions while uncovering lesser-known facets of this enduring legacy.

The Enduring Appeal of Ganesh in Urdu Verse

Urdu literature, born from the confluence of Persian, Arabic, and local Indian languages, has often embraced Hindu deities as metaphors for universal virtues. Lord Ganesh, known in Urdu as “Ganesh” or “Vighnaharta” (remover of hurdles), symbolizes intellect and auspicious starts—themes that resonate deeply in a poetic tradition steeped in philosophy and spirituality. Poets have invoked him not just in devotional contexts but as a beacon of harmony in a multicultural society. This tradition dates back centuries, with verses composed for festivals, personal reflection, and communal celebrations.

In regions like Maharashtra, where Ganesh holds a special place, Urdu poets have integrated his imagery into their repertoire. During annual celebrations, recitations of poems and “Hamd” (praises traditionally for God) adapt to honor Ganesh, fostering interfaith dialogue.

These gatherings transform public spaces into arenas of shared joy, where the deity’s attributes—such as his role in scripting epic tales—are extolled in flowing couplets.

Such practices underscore how Urdu, often associated with Mughal courts, evolved to embrace indigenous folklore, creating a poetic ecosystem that transcends religious labels.

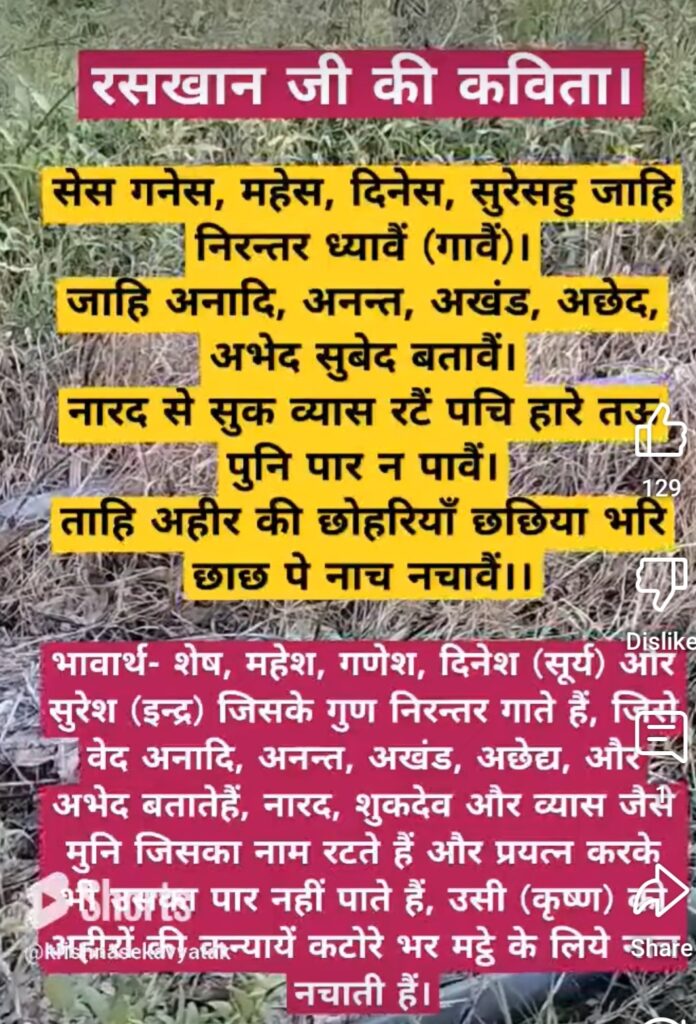

Nazeer Akbarabadi: The People’s Poet and His Ode to Ganesh

At the heart of this tradition stands Nazeer Akbarabadi (1735-1830), an 18th-century Urdu maestro renowned for his accessible, folk-inspired style. Born Wali Muhammad in Agra, Nazeer earned the moniker “people’s poet” for his verses that captured everyday life, festivals, and deities with earthy charm. Unlike the elite ghazal writers of his era, he drew from popular faith, penning tributes to Hindu gods like Shiva and Krishna, reflecting the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb—a cultural blend of Hindu and Muslim elements.

His work on Ganesh, particularly the poem “Ganesh Ji ki Stuti” (Praise of Lord Ganesh), exemplifies this inclusivity, composed around sacred occasions like Anant Chaturdashi.

Nazeer’s poem is a heartfelt invocation, urging devotees to internalize worship.

He begins with a call to the heart: “Avval to dil mein keejie poojan Ganesh Ji. Stuti bhi phir bakhaanie dhan-dhan Ganesh Ji.” (First, worship Ganesh Ji in your heart. Then praise him, hail him.) This sets a tone of inner devotion, emphasizing that true reverence starts within. Throughout, he paints vivid portraits of Ganesh’s form—his crescent-adorned forehead, single tusk, and elephant face—infusing them with wonder and joy. For instance, on the deity’s visage: “Gajamukh ko dekh hota hai sukh ur mein aan-aan. Dil shaad-shaad hota hai main kya karoon bakhaan.” (Seeing the elephant face brings instant joy to the heart. The soul rejoices; how can I describe it?)

Nazeer’s accessible language made his poetry relatable, blending Urdu with Hindi influences to appeal to the masses.

He portrays Ganesh as a benevolent guardian, promising “Riddhi Siddhi aur an-dhan” (prosperity, powers, and endless wealth) to those who meditate constantly: “Har aan dhyaan keejie sumiran Ganesh Ji.” This refrain echoes like a mantra, reinforcing Ganesh’s role as a granter of boons. Beyond aesthetics, Nazeer delves into symbolism, such as Ganesh’s four hands holding items like a noose and axe, representing mastery over desires and obstacles.

His verse on offerings—“Ghee mein mila ke koee jo chadhaata hai aa sindoor. Sab paap usake daalata kar dam ke beech choor.” (Whoever offers vermillion mixed with ghee, crushes all sins in a breath)—highlights ritualistic devotion’s transformative power.

What distinguishes Nazeer’s tribute is its egalitarian spirit. He concludes by surrendering himself: “Too bhee ‘Nazeer’ charanon mein apana jhuka ke maath.” (You too, Nazeer, bow your head at his feet.) This self-inclusion democratizes divinity, inviting all to seek refuge in Ganesh’s grace, regardless of background.

His poetry on festivals like Holi and Diwali further cements his role as a bridge-builder, celebrating India’s pluralistic ethos.

Divine Attributes: Wisdom, Obstacles, and Epic Lore

Urdu tributes to Ganesh often revolve around his core attributes, reimagined through poetic lenses. As the scribe of the Mahabharata—dictated by Vyasa—Ganesh embodies boundless knowledge, a theme poets exploit to explore human intellect’s limits. Nazeer alludes to this in praising Ganesh as “Ilmo hunar mein ek hain aur buddhi ke nidhaan” (One in knowledge and skill, treasure of wisdom), urging devotees to prioritize this over worldly pursuits.

Other verses emphasize his obstacle-removing prowess. In Nazeer’s work, Ganesh’s mouse vehicle (Moosa savaari) becomes a metaphor for humility conquering ego: “Moosa savaaree ko hai ajab khoob benazeer. Kya khoob kaan panje hain aur dum hai dil pajeer.” (The mouse ride is uniquely incomparable. Lovely ears, claws, and tail fill the heart with joy.) This imagery contrasts Ganesh’s grandeur with his modest mount, symbolizing how wisdom tames the restless mind. Poets also invoke his parentage as Shiva and Parvati’s son, portraying him as a compassionate intermediary: “Vah hainge ajab aan se Shiv Gauri ke laala. Sur nar muni bhee kahate hain vo deen dayaala.” (He is the wondrous son of Shiva and Gauri. Gods, men, and sages call him merciful to the humble.)

These elements not only authenticate devotion but also philosophize life’s challenges, making Ganesh a timeless muse for introspection.

Festival Rhythms: Ganesh Chaturthi and Poetic Celebrations

Ganesh Chaturthi, the grand festival marking Ganesh’s birth, amplifies these tributes. In Maharashtra, Urdu poets gather to recite verses, blending Hamd with bhajans in a symphony of unity. This tradition, alive today, sees poets like those in Mumbai’s literary circles composing fresh odes. For instance, contemporary Shayari often wishes prosperity: “Phool ki shuruvat kali se hoti hai, Zindgi ki shuruvat pyar se hoti hai” (A flower’s start is from a bud, life’s from love), tying into Ganesh’s auspicious role.

Nazeer’s poem, tied to Anant Chaturdashi (the immersion day), complements this, envisioning celestial beings like Brahma and Indra performing aarti: “Sanakaadi soory chandr khade aaratee karen. Aur sheshanaag gandh kee le dhoop ko dharen.” (Sanak and others, sun and moon perform aarti. Sheshnag offers fragrant incense.) Such vivid scenes mirror festival processions, where poetry enhances immersion rituals.

Echoes from Other Voices: Broader Urdu Contributions

While Nazeer leads the chorus, others amplify it. Gulzar Dehlvi, a 20th-century luminary, metaphorically referenced Ganesh in Hamd, likening divine wisdom to the deity’s intellect.

Poets like Firaq Gorakhpuri and Ghalib, though not direct devotees, infused their work with syncretic motifs.

Earlier figures, such as Amir Khusrau, paved the way with Sufi-infused praises of saints and gods, indirectly influencing Ganesh tributes.

In modern times, social media abounds with Urdu wishes for Ganesh Chaturthi, like: “O lord of wisdom and progress,” blending tradition with contemporary expression.

This evolution keeps the tradition vibrant, especially in diaspora communities.

Cultural Harmony and Lasting Relevance

These tributes exemplify India’s composite culture, where Urdu—once the language of courts—became a vessel for interfaith harmony. Nazeer’s inclusive approach challenged divides, promoting unity amid colonial tensions. Today, amid polarized discourses, such poetry reminds us of shared roots. Recent commemorations, like those honoring Nazeer in 2025, revive his verses, fostering dialogue.

In essence, Urdu’s odes to Ganesh transcend religion, celebrating human aspirations for wisdom and peace.

As Nazeer implores, “Jo jo sharan mein aaya hai keenha use sanaath” (Whoever seeks shelter, he protects them), these hymns invite all to embrace Ganesh’s grace.

In a world of obstacles, these poetic tributes endure, guiding us toward enlightenment and unity.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai