The Politics of Renaming : A Convenient Distraction in Modern India

The renaming of public infrastructure, geographical locations, and major institutions has become a conspicuous—and increasingly preferred—feature of contemporary Indian governance. Streets, railway stations, airports, towns, and entire cities are routinely rechristened under the pretext of celebrating local culture, honouring forgotten heroes, or restoring historical pride. Yet beneath this façade of cultural revival lies a far more calculated political design: a selective rewriting of history that appeals to particular constituencies while deftly diverting public attention from unresolved developmental challenges.

The Siren Call of Renaming

India’s post-Independence decades have seen steady efforts to replace colonial-era nomenclatures. Metropolitan centres like Mumbai (formerly Bombay), Chennai (formerly Madras), and Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) led these linguistic transitions. But in recent years, the momentum has accelerated dramatically, extending beyond major cities to smaller towns and everyday public spaces.

Renamed Towns and Cities: The transition of Allahabad to Prayagraj, Aurangabad to Sambhajinagar, and Gaya to Gayaji are among the most visible examples.

Renamed Railway Stations: Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus (formerly Victoria Terminus) and the rechristening of Mughal Sarai Junction as Deendayal Upadhyaya Junction signal a systematic trend.

Renamed Roads: Across urban India, colonial-era road names have been replaced—such as Delhi’s Dalhousie Road becoming Dara Shikoh Road—under the banner of honouring overlooked cultural icons.

While such changes are advertised as efforts to reclaim indigenous identity, the underlying impulse is often deeply political. Renaming serves as an easy tool to smooth over uncomfortable historical narratives and selectively erase periods deemed ideologically inconvenient or “foreign.” It is symbolic politics at its most efficient immediate, inexpensive, and guaranteed to dominate public discourse.

But what, one must ask, is the developmental value of such exercises? Did renaming Gurgaon to Gurugram improve public transport? Did rechristening Aurangzeb Road address Delhi’s pollution? The reality is unavoidable: renaming is a low-cost spectacle that allows governments to sidestep the far harder business of governance.

The Bombay–Mumbai Controversy: An Institutional Hurdle

The enduring tension between historical nomenclature and contemporary identity recently resurfaced in Maharashtra. During a function at IIT Bombay, Union Minister Jitendra Singh’s reference to the institution by its official name inadvertently rekindled the decades-old Bombay-versus-Mumbai debate. Maharashtra’s then-Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis immediately expressed openness to renaming IIT Bombay as IIT Mumbai. Raj Thackeray’s Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) quickly amplified the sentiment.

Yet this debate exposes an important institutional contradiction. If IIT Bombay must become IIT Mumbai, must the Bombay High Court undergo a similar change? Should IIT Madras become IIT Chennai, or the Madras and Calcutta High Courts be renamed in line with their cities’ updated identities?

The hyper-politicisation of such nomenclature reveals the nature of the exercise. It is theatre—an attempt to channel public emotion into symbolic debates that overshadow economic stagnation, unemployment, infrastructure deficits, and social inequality.

Unearthing History: Whose City Is It Anyway?

The politics of renaming becomes even more troubling when it ignores the complex, multi-layered histories that underpin modern cities. Mumbai’s story, in particular, is one of migration, settlement, and collaborative development across communities and centuries.

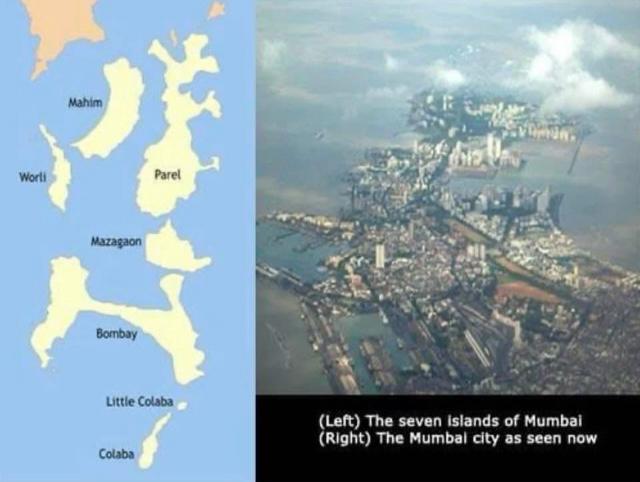

Historical records trace the original seven islands—Colaba, Mazagaon, Old Woman’s Island, Wadala, Mahim, Parel, and Matunga-Sion—to the Mauryan Empire of Ashoka the Great. Their ancient lineage survives in the Kanheri, Mahakali, and Elephanta caves. The islands later came under the Gujarat Sultans, whose imprint remains in structures such as the dargahs at Mahim and Haji Ali. The Portuguese rechristened the region Bom Baia (“Good Bay”) and built early forts.

In 1662, the islands entered British possession as part of Portuguese Princess Catherine of Braganza’s dowry to King Charles II. The East India Company, leasing the islands for £10 a year, played a pivotal role in transforming the archipelago into the emerging port city of Bombay.

The city’s foundations were shaped by its diverse inhabitants:

•The Kolis, its earliest known residents, worshipped Mumbaidevi and referred to the area as Mumbai.

•The first Parsi settler, Dorabji Nanabhoy Patel, arrived in 1640, while his son Rustomji bravely defended Bombay against the Siddi of Janjira in 1689–90 with Koli support.

•Governor Gerald Aungier laid administrative structures, inviting Gujarati traders, Parsi shipbuilders, and Muslim and Hindu manufacturing communities to settle.

•Herculean reclamation projects—Hornby Vellard (1784), Sion Causeway (1803), and Colaba Causeway (1838)—tied the islands into a cohesive landmass.

•Lady Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy’s funding of the Mahim–Bandra Causeway (1845), with the stipulation that the public never be charged a toll, stands in stark contrast to the high-toll Bandra–Worli Sea Link today.

As the city grew, the Wadias built its docks; the Tatas endowed it with the Taj Mahal Hotel and Air India; Godrej pioneered vegetarian soaps; and Gujarati, Kutchi, Parsi, and Marwari entrepreneurs established textile mills that drew migrant Maharashtrians as the industrial workforce. Premchand Roychand, a Gujarati broker, established the Bombay Stock Exchange and funded the Rajabai Tower.

Every community, except the indigenous Kolis, came to Mumbai from elsewhere. Mumbai is thus not the cultural property of any one linguistic, religious, or caste group. It is a shared inheritance an Indian city in the broadest, most inclusive sense.

References

•Edwardes, S.M. The Rise of Bombay: A Retrospect. Oxford University Press, 1902.

•Da Cunha, J. Gerson. The Origin of Bombay. Asian Educational Services, 1993 (reprint).

•Dwivedi, Sharada; Mehrotra, Rahul. Bombay: The Cities Within. Eminence Designs, 1995.

•Kosambi, Meera. Bombay in Transition: The Growth and Social Ecology of a Colonial City. Routledge, 1994.

•Munshi, Kanaiyalal. Gujarat and Its People. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1960.

•Government of India notifications on city and station renaming (Ministry of Home Affairs Archives).

•The Gazetteer of Bombay City and Island (Relevant Volumes).

•Records of the Bombay Municipal Corporation (BMC).

•Historical documents pertaining to Portuguese and British rule, including records of King Charles II’s dowry.

•Maharashtra State Gazette notifications on renaming of Aurangabad–Sambhajinagar and Allahabad–Prayagraj.

•”History of Bombay High Court,” Bombay High Court official website.

•”History of the Tata Group,” Tata Central Archives.

•”The Wadias of Bombay Dockyard,” National Maritime Museum of India.

•”Rajabai Tower and University of Mumbai,” Mumbai University Archives.

~Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai.

~Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai