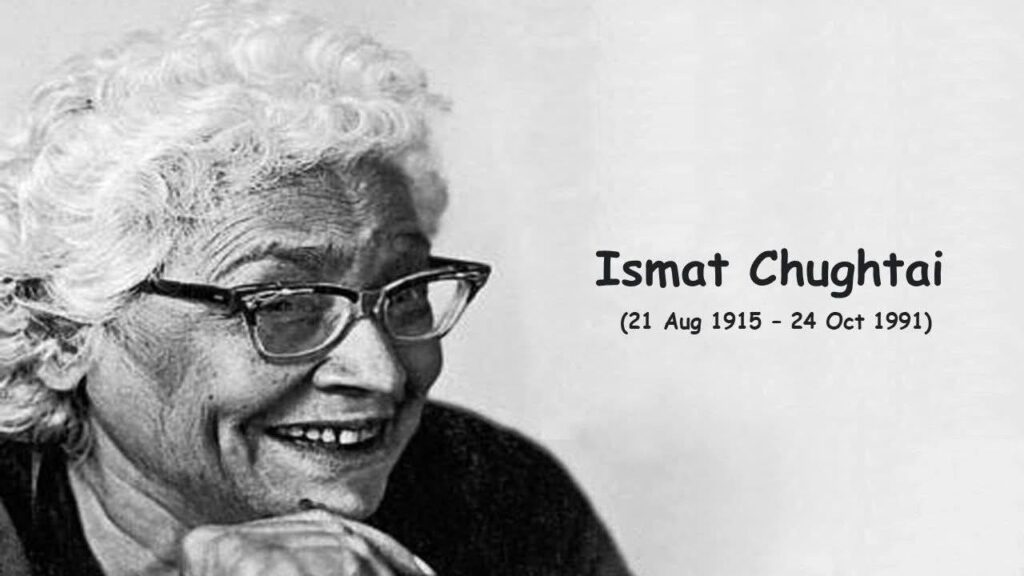

Tribute to the legendary Urdu writer Ismat Chughtai on her 110th birth anniversary

*Ismat Chughtai at 110: The Uncompromising Pen that Shook Urdu Letters*

*Marking the 110th birth anniversary of the fearless chronicler of women’s inner lives and society’s hypocrisies.*

*A Rebellious Birth, A Rebellious Voice*

On *August 21, 1915*, in the small town of *Badaun, Uttar Pradesh*, a little girl was born who would later unsettle, provoke, and revolutionize the world of Urdu literature. Her name: *Ismat Chughtai*.

For a girl born into a conservative Muslim household, in a colonial India where women’s education was often a rarity, her destiny could have been silent domesticity. Instead, she challenged patriarchy head-on, wielding her pen like a sword, but its cuts were lined with humour, empathy, and piercing realism.

*Lihaaf and the Spark of Controversy*

In *1942*,

Chughtai published a short story called *”Lihaaf” (The Quilt)*. What followed was literary history. The piece, which depicted female loneliness and same-sex desire within the four walls of a respectable household, tore through the polite hypocrisies of Indian society. Predictably, it provoked rage — and a *landmark obscenity trial* was slapped on its author. But Chughtai did not apologize, retract, or fall silent. She *faced the court with fire in her eyes* and emerged acquitted, turning the story into a manifesto of boldness. The trial itself is now remembered less as a condemnation of her and more as testimony to her courage.

*”Lihaaf”* was not merely a story about hidden sexuality. It was about *the suffocation of women in bourgeois households*, where their bodies, pleasures, and desires were tightly policed yet clandestinely burning. Chughtai’s genius lay in her ability to merge the personal with the political, to read the intimate in the framework of society’s broader constraints.

*The Crooked Lines of Life*

If “Lihaaf” made her controversial, her novel *”Tedhi Lakeer” (The Crooked Line)* revealed her breadth. Published in 1945, the semi-autobiographical novel follows the protagonist Shama, a young woman negotiating rebellion, love, and the contradictions of modern life in colonial India. Critics hail it as *one of the earliest feminist bildungsroman* in Urdu literature. It traced not only the evolution of a woman but also the seismic changes in India’s intellectual and social landscape before Independence.

By writing about women who desired, doubted, rebelled, and stumbled, Chughtai was not merely creating characters.

She was *documenting the female condition with an honesty unknown to Urdu fiction until then*.

*Ziddi, Fearless, Unrelenting*

Her novel “Ziddi” (Stubborn), published in 1941, epitomized Chughtai’s tenacity. The title alone captured her personality—unyielding to societal diktats, challenging norms at every step. Later adapted into a successful Hindi film in 1948, with music by Khemchand Prakash, it also showcased Chughtai’s parallel career as a *screenwriter* in Bombay cinema, where she collaborated with leading filmmakers and lent her sharp observations to the silver screen.

*A Progressive Pen*

Chughtai’s career cannot be understood without the larger context of the *Progressive Writers’ Movement*, an intellectual wave that swept Urdu and Hindi letters in the 1930s and 1940s. Alongside luminaries such as *Sajjad Zaheer, Saadat Hasan Manto, Krishan Chander, and Rajinder Singh Bedi*, she pushed literature toward the real, the raw, and the socially urgent.

Yet Chughtai retained her own distinctive voice: where many progressives wrote about the proletariat and class struggle, *she rooted her gaze in the domestic sphere, especially the feminine domestic sphere, exposing how class and gender intersected inside homes*.

*Language of Wit and Razor*

Her writing style is notable for *earthy idioms, biting wit, and colloquial cadences*. She wrote not for pedantic critics, but for readers who lived the struggles she described. Ordinary women recognized themselves in her characters—the restless housewife in “Lihaaf,” the adolescent girl in *”Tedhi Lakeer” (The Crooked Line,”)* the spirited students, servants, begums, and widows who populate her short stories. Each was crafted not in abstraction but rendered with *flesh, sighs, and contradictions*.

As one critic observed, reading Chughtai was like *sitting at the courtyard of a bustling house, listening to gossip, laughter, and suppressed cries*_but presented with artistry that elevated them into social commentary.

*The Obscenity Debate and Beyond*

The obscenity trial of “Lihaaf” is often remembered as the defining storm of Chughtai’s career. But she herself dismissed it later, remarking that she never wrote for scandal but always “what I saw and felt.” For her, literature was about *honesty, not provocation for its own sake*. She believed in breaking silence on areas others kept hushed—sexuality, class exploitation, religious hypocrisy, colonial subjugation. That honesty made her radical.

*Cinema and Later Years*

In the 1940s and ’50s, Chughtai expanded her creativity into *Hindi cinema*, scripting films such as *Arzoo* and *Garam Hawa*. Cinema gave her a broader platform, but her soul remained tethered to the written word. Over the decades, she published *more than a dozen novels, countless short stories, memoirs, essays, and plays*. Works like *Ek Qatra-e-Khoon*, *Tedhi Lakeer*, *Dil ki Duniya*, and her memoir *Kaghazi Hai Pairahan* further etched her place in literary history.

Her sharp insights and refusal to compromise earned her the *Padma Shri in 1976*, recognition by the Indian state yet too modest compared to her towering stature.

*Legacy of a Literary Maverick*

Ismat Chughtai passed away in *October 1991 in Mumbai*, but her writings remain *startlingly fresh*. Issues she addressed—female suppression, gendered silences, societal hypocrisies—have not vanished. In fact, many writers, scholars, and activists today draw directly on her courage and candor.

To remember Ismat on her *110th birth anniversary in 2025* is to realize that literature is not just art—it is an act of rebellion, a record of lived truth, and a tool for emancipation. Chughtai turned her pen into such a weapon, but its sharpness was always accompanied by humanity, humor, and empathy.

*Still Reading Ismat*

Even today, when readers pick up *Lihaaf*, they may be jolted by its boldness. When they read *Tedhi Lakeer*, they encounter not only Shama’s crooked journey but also their own fractured struggles. When they hear of her trial, they recognize the timeless battle between creativity and censorship.

Ismat Chughtai was not just a writer—she was a phenomenon, a movement, a stubborn refusal to look away. She wrote what no one dared put on paper, and in doing so, she ensured that *Urdu literature, and Indian literature at large, could never again remain the same*.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai