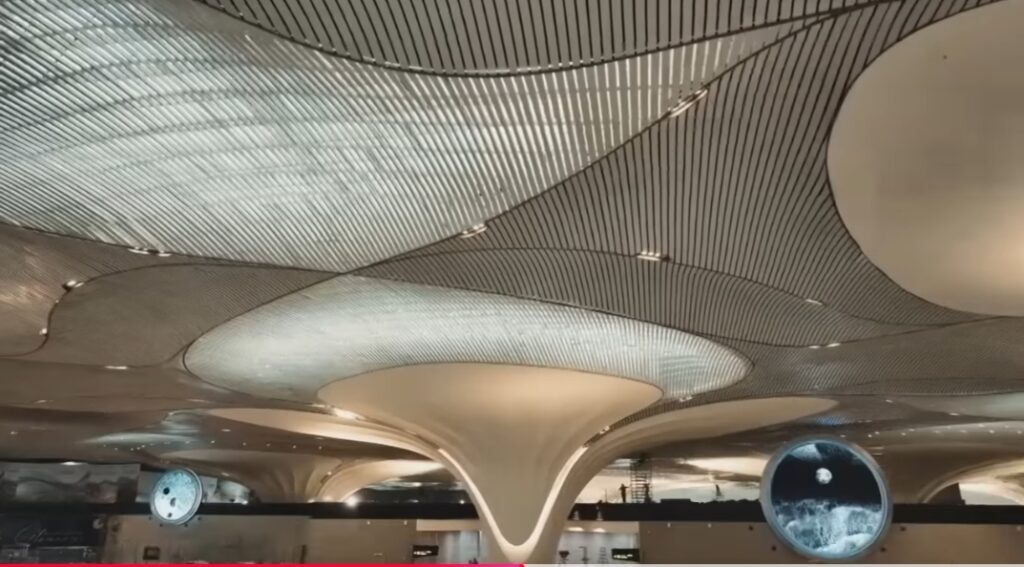

The newly inaugurated Navi Mumbai International Airport should have been a moment to celebrate architectural brilliance, urban foresight, and modern connectivity. Instead, it has emerged as a cautionary tale—of visionary creativity undermined by indifferent governance, of a globally renowned architect erased from public recognition. Zaha Hadid, the Iraq‑born British pioneer whose design genius shaped this landmark infrastructure, did not live to see its completion. She passed away in 2016, at the peak of her career. Yet even in absence, her imprint on the project remains indelible. What does not remain is the respect she deserved—either in the speeches from India’s leaders during the inauguration or in the very public transport infrastructure she considered fundamental to any serious airport design.

The Missing Voice at the Inauguration

The official launch ceremony on 8 October 2025, attended by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Deputy Chief Minister Eknath Shinde, was long on political flattery and short on acknowledgment of genuine contributors. Amid the proclamations of national achievement, there was no mention—let alone tribute—to the architect whose firm conceived the airport’s bold aesthetic. Shinde’s speech, steeped in sycophancy toward the Prime Minister, fell to depths both tasteless and telling. The underlying message: political ownership counts far more than professional authorship.

Modi, characteristically assuming the role of chief visionary, spoke of scale and ambition but avoided the simple gesture of naming Zaha Hadid. This silence, in one of India’s most ambitious urban projects, contrasts sharply with the cultural practice of entrusting recognition where it is due—be it to engineers, designers, or community champions.

A Global Standard in Design, A Local Failure in Delivery

Hadid was no stranger to transport‑centric architecture. Heathrow’s model—an integrated web of metro, rail, and bus connections—embodied her commitment to accessibility. Such seamless integration is absent in Navi Mumbai’s final reality. The government advertisements published yesterday boldly claimed a “truly multi-modal airport” with connectivity via metro, suburban rail, and water taxis. This is categorically untrue.

In reality, the airport site is marooned, surrounded by distances that mock the idea of convenience. Panvel, Belapur, and Vashi lie at awkward remove. Even with the trans‑harbour link, access resembles a logistical challenge more than effortless travel. No metro lines presently connect, no suburban trains halt nearby, no bus corridors are functional. The grand promises will take years—if they materialise at all.

The Ghost of the Metro Plan

To compound the irony, the Detailed Project Report (DPR) for the metro line to the airport was only recently submitted to the government—after the inauguration. The plan’s scale is significant: a 34.89‑km corridor costing an estimated ₹23,000 crore. Cidco, the nodal agency, seeks viability gap funding from central and state governments alongside a private BOT partner. Experience with Mumbai’s Metro Line 3 reveals a sobering truth: infrastructure of this magnitude can take years, if not decades. By the time the metro reaches this airport, the city’s mobility priorities may have shifted entirely.

Meanwhile, day‑to‑day commuters face another blow. Mumbai’s already battered bus service appears further sidelined in favour of prestige metro projects. This trade‑off sacrifices the connectivity lifeline millions depend upon—a fact Hadid, mindful of practical mobility in her designs, would have found unacceptable.

The Contrast With Riyadh

Perhaps the most damning comparison comes from Riyadh. Flush with oil wealth, Saudi Arabia still prioritised public transport in the form of a visually stunning metro network—designed by Hadid’s team following her death. While Riyadh moves toward integrated mobility, Navi Mumbai’s airport stands as a luxurious shell without arteries. This is not a question of funds but of vision, planning discipline, and respect for citizens’ functional needs.

The neglect is doubly shameful for being self-inflicted. Public transport systems have been long deferred, curtailed, or undermined in pursuit of fragmented, prestige-heavy construction. Nothing in Hadid’s body of work suggests she valued vanity over utility. To deliver her airport design without the supporting systems she considered integral is almost an act of architectural betrayal.

Silencing Histories in the Name Game

The sense of erasure extended beyond Hadid. The demand to name the airport after the late D.B. Patil—a local legend representing the Peasants and Workers Party—was set aside under opaque political calculus. Patil was known for sincerity and simplicity, values that clash starkly with the spectacle of yesterday’s launch. Though lip service was paid to his memory, the decision to bypass naming rights in his favour has angered the Agri community, which may react strongly.

Such decisions reveal a deep contradiction: leaders frequently invoke historical figures like Shivaji as emblems of defiance and self‑respect, but operationally they diminish local histories when those do not align neatly with current power narratives.

Lies Written in Advance

The grand claims in the front‑page advertisements—of integration by metro, suburban rail, and water taxi—were not future visions but *contemporary falsehoods*. It is not difficult to verify that no such connectivity exists today. Authorities assume they can rebrand absence as achievement because these items reside in technical masterplans. This is distinct from aspirational nationalism (projections of India as a future global power); here the deceit concerns basic present conditions.

When the airport becomes operational in two months, passengers will be faced not with the touted multimodal network but with the reality of negotiating private vehicle traffic, longer travel times, and congestion spillover into nodes already struggling under commuter strain.

Ridicule in Waiting

Hadid’s name, when mentioned globally, commands association with graceful design, functional foresight, and civic respect. Airports under her vision—from Beijing Daxing to innovative regional designs—reflect more than architectural bravado; they resolve logistical travel pain points.

The Navi Mumbai project now risks becoming the inverse: a gleaming building whose practical access is so poor it invites mockery, not admiration. International travellers arriving at this showcase of Indian ambition will encounter the irony instantly: an airport of global scale stranded in regional inaccessibility.

The Unsung Hero of Navi Mumbai

To narrate Zaha Hadid’s exclusion from the inauguration speeches is to capture not merely an oversight but a cultural malaise. Recognizing intellectual and creative labour is fundamental to civic respect. Ignoring that labour—a habit entrenched in India’s large public projects—robs them of their human dimension.

An airport is not just an engineering feat; it is the culmination of thousands of hours of design iteration, environmental negotiation, and aesthetic balance.

Hadid gave this airport its identity. She envisioned a transport‑embedded gateway to the metropolis. Without her, the project’s international stature shrinks. Yet for all her work, her name was absent from the litany of thanks, drowned in political drumbeats.

Tribute Where It’s Due

Every infrastructure project carries two truths—the tangible reality of platforms, runways, and beams, and the intangible ethos of the design itself. Navi Mumbai International Airport has achieved the former but is forfeiting the latter. By omitting Zaha Hadid from its celebratory stage and by failing to deliver the connectivity that was central to her vision, India has done its architect a disservice.

It is not too late to correct course. Authorities can still honour her publicly, accelerate promised transport links, and ensure the airport genuinely matches the vision she imagined. To do otherwise is to let the building stand as a monument not to forward-looking design, but to the gap between India’s rhetoric and its delivery.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai